How industry associations and other business organisations can become a standards setter

23/11/2017

I am in the process of interviewing CEOs of major companies around the world for a new book I am writing about enduring leadership in corporate sustainability. One of the issues that keeps coming up is trust – or rather, the lack of it. How do businesses restore trust? Trust in their own business; trust in their sector; trust in business in general.

Edelman, of course has been tracking trust in business and other sectors in their annual Trust Barometer, since the Millennium. This year was the first where trust in all four sectors studied: business, government, NGOs, media declined simultaneously. The 690th Lord Mayor of London sworn in on November 10th has declared the “business of trust” one of the priorities for his year in office.

Behaving responsibly, being corporately responsible and encouraging other businesses to follow suit, is fundamental to restoring trust in individual businesses. Companies must take a leadership role on their own, but also be willing to work collectively in partnership with their peers and competitors to achieve industry-wide progress. This is why Corporate Responsibility Coalitions have emerged around the world since the 1970s and especially from the 1990s onwards and why more traditional trade and industry associations have also established focused programs in this area. Jane Nelson from the Corporate Responsibility Initiative at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government and I wrote about these coalitions in our 2013 book: “Corporate Responsibility Coalitions: The Past, Present and Future of Alliances for Sustainable Capitalism. The first generation of coalitions, were predominantly general in their membership and scope. Subsequently, and especially since the Millennium, a second generation of industry-specific and issue-specific coalitions and multi-stakeholder initiatives have emerged such as the International Council of Mining and Metals, the Sustainable Shipping Initiative, the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights, and the CEO Water Mandate, to name just a few.

Simultaneously, the old binary choice: markets or regulation has become much more nuanced. Individual companies committing themselves voluntarily to higher standards of behaviour is a form of self-regulation. Albeit the costs of failing to hit a target are less draconian if a company is trying to innovate and take a leadership role than if the corset of the law has been applied. Groups of companies coming together to develop and commit themselves to industry-wide voluntary standards like the Conflict-Free Gold Standard, is a form of collective self-regulation linked to the concerns of others elsewhere in the supply chain – and often developed with participation from civil society organizations.

Prof Atle Midttun of the Norwegian Business School highlights that sometimes sovereign governments “bless” these standards – for example, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative – in the case of the EITI sovereign governments have to own and lead the process – albeit they cannot be recognised as compliant without the participation and blessing of Civil Society Organisations and business. Midttun describes this as a form of “collaborative governance” or what the writer Simon Zadek calls “partnered governance.”

Midttun situates this collaborative or partnered governance in the context of political philosophy as an extension of Rousseau’s Social Contract; and as linked to management theory such as Prof Ed Freeman and Stakeholder Theory of the Firm.

These new collective, self-regulatory standards are now part of “soft law” and deserve serious attention both in business schools and in schools of public policy. This is why my friend and colleague Jane Nelson from Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government and I from a school of management – Cranfield – were so enthusiastic about Edward Bickham’s willingness to write about the emergence of the Conflict-Free Gold Standard.

We all owe a great debt of gratitude and appreciation to Edward for this study. Jane and I also want to thank the World Gold Council for giving Edward such free access to all the necessary documentation and the freedom to produce a really comprehensive and honest study. This is industry-wide leadership and thoughtful stakeholder engagement at its best. The result is an impressive report, which adds importantly to the collaboration literature and should be of interest both to Schools of Public Policy and Schools of Management and Business. The report should also help companies in other sectors wanting to establish similar standards for their industry.

The case study demonstrates inter alia the importance of:

|

Above all, the case study illustrates the vital and inter-locking roles of both individual leadership and institutional leadership in developing a shared vision and practical solutions to addressing complex, systemic challenges. Leadership on human rights and sustainability issues by business executives is more important than it has ever been, and this example from the gold mining sector illustrates what is possible.

Edward’s paper focuses on the multi-dimensional creation of the CFGS. It is not an evaluation of the effectiveness of the CFGS and now that it is five years old, that is possibly a task for others to take up.

Based on REMARKS TO WORLD GOLD COUNCIL ‘The role of industry associations in standard setting’ DINNER, WASHINGTON DC, NOV 14TH 2017.

Read the press release about the report here: https://www.cranfield.ac.uk/som/press/conflict-free-gold-standard-report-offers-key-insights-on-corporate-responsibility

Categories & Tags:

Leave a comment on this post:

You might also like…

Keren Tuv: My Cranfield experience studying Renewable Energy

Hello, my name is Keren, I am from London, UK, and I am studying Renewable Energy MSc. My journey to discovering Cranfield University began when I first decided to return to academia to pursue ...

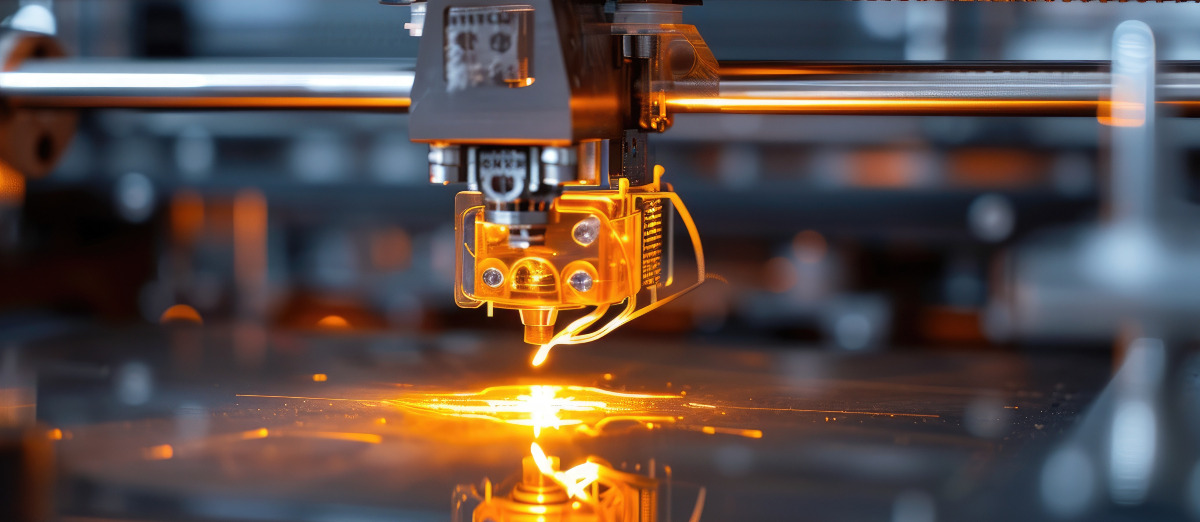

3D Metal Manufacturing in space: A look into the future

David Rico Sierra, Research Fellow in Additive Manufacturing, was recently involved in an exciting project to manufacture parts using 3D printers in space. Here he reflects on his time working with Airbus in Toulouse… ...

A Legacy of Courage: From India to Britain, Three Generations Find Their Home

My story begins with my grandfather, who plucked up the courage to travel aboard at the age of 22 and start a new life in the UK. I don’t think he would have thought that ...

Cranfield to JLR: mastering mechatronics for a dream career

My name is Jerin Tom, and in 2023 I graduated from Cranfield with an MSc in Automotive Mechatronics. Originally from India, I've always been fascinated by the world of automobiles. Why Cranfield and the ...

Bringing the vision of advanced air mobility closer to reality

Experts at Cranfield University led by Professor Antonios Tsourdos, Head of the Autonomous and Cyber-Physical Systems Centre, are part of the Air Mobility Ecosystem Consortium (AMEC), which aims to demonstrate the commercial and operational ...

Using grey literature in your research: A short guide

As you research and write your thesis, you might come across, or be looking for, ‘grey literature’. This is quite simply material that is either unpublished, or published but not in a commercial form. Types ...