Helping to revive wargaming in the Royal Navy

17/12/2019

Wargaming played a vital role during World War Two in helping Royal Navy ship and submarine commanders to outthink their opponents in the Battle for the Atlantic and keep convoy supply routes to the UK open.

By simulating forces and movements in a specific setting, wargames can help to prepare military commanders for the kind of tactical and operational decisions they may need to make when fighting real conflicts.

There are lots of examples of where wargaming has helped in real world situations. Sticking to the maritime domain, there’s some evidence that Nelson explained his battle plan for Trafalgar to his captains with a form of wargame.

More recently, the Western Approaches Training Unit was established in 1943 to help win the Battle of the Atlantic. The wargame floor was set up in Liverpool and convoy captains practised manoeuvres to defeat German u-boats. Even the advent of homing torpedoes was assessed during these wargames and tactics developed to overcome the new technology. The US Navy also used wargaming a lot in the war in the Pacific during WW2.

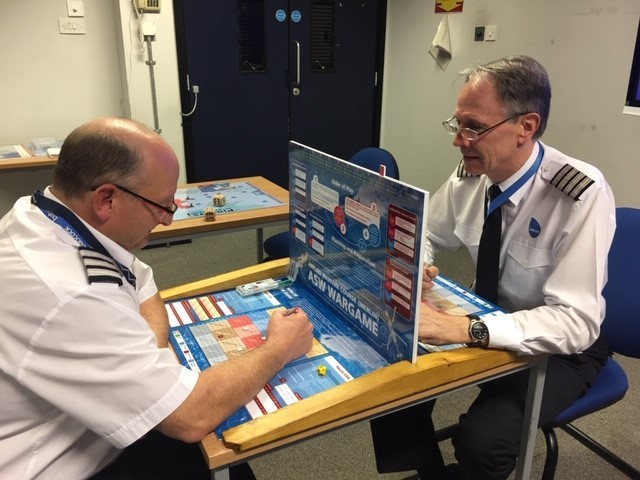

As part of my ‘day-job’ as a helicopter simulator instructor at RNAS Culdrose in Cornwall, I am now using knowledge learnt at Cranfield to drive a wargaming revival in the Royal Navy.

When I did my Defence Simulation and Modelling MSc at Cranfield Defence and Security, I included the Wargaming and Combat Modelling module.

At the time (in 2006), the Royal Navy wasn’t using wargaming for training very much and the groundbreaking work that was done in 1943 at the Western Approaches Training Unit had been lost as a skill at unit level.

In 2017, the Development, Concepts and Doctrine Centre at Shrivenham published their Wargaming Handbook with a forward by Vice Chief of Defence Staff encouraging the MOD to regenerate the culture of wargaming.

The VCDS’s words came down the chain of command and reached the Royal Navy unit that I work for as a Reservist (Merlin Helicopter Force HQ) and I was asked to attend UK Defence Academy’s Introduction to Wargaming course, run as a one-off trial run. I was then asked to allocate some of my Reservist’s time to write a wargame for Merlin Helicopter Force to see how it could be used for training.

After some trial and error, help from Dstl wargamers, and attendance at the wargaming conference (Connections UK), the art and science of wargaming became part of my ‘day job’ as a simulator instructor working for Babcock. I ended up as the go-to person for designing wargames for training.

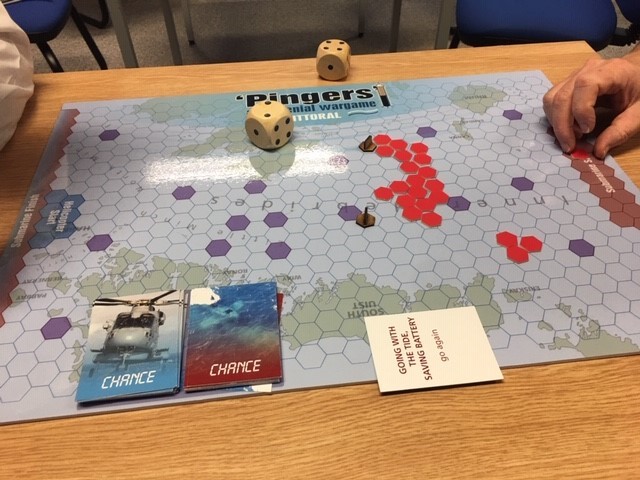

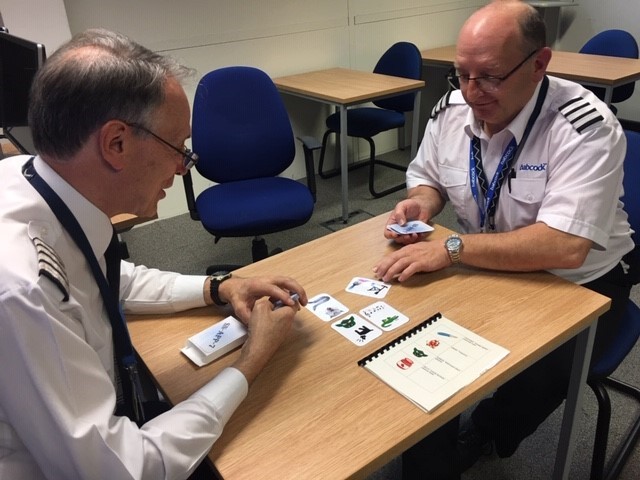

Babcock has been working on a new training course for the Royal Navy and I’ve embedded wargames into the syllabus, using various constructs to deliver training material. These include card games as simple as Snap to poker, to mini-wargames based on Battleships and Go to full Red Cell vs Blue Cell closed wargames.

Specific games are designed to meet the key learning points and enabling objectives, so when selecting methods and media during training design you pick the game mechanics best suited for the task.

A training task for knowledge acquisition could be as simple as a game based on Snap where you want visual recognition of something to be connected with a name or phrase. The game is supporting repetition, relevance and recency as an aid to memory development.

If you want to train the application of more abstract ideas – for example warfare tactics – then a wargame can be designed to provide an abstracted scenario to allow those tactics to be employed with reasonable outcomes. The game gives players an opportunity to see a time-compressed series of events unfold, reflect and then play again, maybe from the opposition’s point of view next time.

Wargame rules are developed to constrain the players by real-world factors. After defining the training need, the design process follows on with the maths and physics of the real world, the current equipment, or known human limitations. The rules encompass those ‘facts’ and then use game mechanics – turn taking, probability assessment with dice, look-up tables, random chance cards, and others, to make the game live.

The opposing player is essential – the enemy gets a vote and adds more unplanned events that have to be reacted to. Computer games are good where real-world equipment interfaces need to be trained, but artificial intelligence isn’t as challenging or surprising as a human being, and the debrief is so much more enlightening when you can talk to the opposition afterwards.

The wargaming revival in the MOD is underway, regenerating a hard-won skill from some of the Royal Navy’s darkest days and delivering engaging, meaningful training to a new generation of anti-submarine warfare specialists.

Categories & Tags:

Leave a comment on this post:

You might also like…

My journey to Cranfield as an FIA Motorsport Engineering Scholar

"You don’t need to fit a stereotype to succeed in engineering or motorsport. You need curiosity. Resilience. And the confidence to take up space." In this blog, Sanya Jain, current MSc student and FIA ...

‘Getting started with Bloomberg’ training – discover the power of Bloomberg terminals

Perhaps you've heard people talking about Bloomberg or heard it mentioned in the news and are wondering what all the fuss is about? Why not come along and find out at our Getting started with ...

Commonwealth Scholarships play a critical role in developing sustainability and leadership in Africa

Q&A with Evah Mosetlhane, Sustainability MSc, Commonwealth Distance Learning Scholar What inspired you to pursue the Sustainability MSc at Cranfield? I was inspired to pursue the Sustainability MSc at Cranfield because of the university’s ...

How do I reference a thesis… in the NLM style?

You may be including theses within your research. When you do so you need to treat them in the same way as content taken from any other source, by providing both a citation and a ...

Introducing… Bloomberg Trade Flows

Are you interested in world trade flows? Would it be useful to know which nations are your country's major trading partners? If so, the Bloomberg terminal has a rather nifty function where you can view ...

Cranfield alumni voyage to the International Space Station

Seeing our alumni reach the International Space Station (ISS) has a ripple effect that extends far beyond the space sector. For school students questioning whether science is “for them”, for undergraduates weighing their next ...

There are some great books on Wargaming and they often include a description of the process to be followed to make your own games. The diagrams of the process loop around, so that having designed, built, tested and deployed a wargame then there’ll be some feedback that joins back into more designing, building and testing. That’s certainly been true for me. The feedback has varied from “too much detail, took too long to learn”, to “great game, but if this detail was added it’d be even better”. So, what this underlines to me is that a wargame is only a ‘best fit’ for the training audience and the key learning points that it was designed for. If you start to take it out of context the audience may not receive full benefit from it and the significant points of learning may be lost.

The other aspect that came in the feedback was the importance of the surrounding course structure and organisation that the game has to fit in. A Top Trumps game was developed to include a period of student research in preparation for the game, but the schedule cut the time available to play the game and the feedback was ‘negative’. I’d made the students do all the ‘boring’ research bit, but hadn’t rewarded them sufficiently with the fun and learning reinforcement part of playing the game. We’re dealing with human beings in a training system and I hadn’t fully appreciated their perspectives.

There are so many game mechanics to be used in wargames for training. I’d be really interested to hear what others have done.

In the last year we’ve just kept making more games for training: card-games, board-games and web browser computer-games. It was suggested that we put in a bid for Idea Of The Year, grouping up all our games and highlighting the thinking that lead us in this direction.

Here’s our submission video for the competition: https://youtu.be/fuS0lGcn7UI

I’m very proud to say that the team of four that I worked with on all these games, won the ‘Continuous Improvement’ category in Idea Of The Year 2020 for the bid “Games For Tactical Training”.

Hope to be doing more with ‘games’ in 2021.

Six months on and we’ve run two more 7 week courses developing RN aircrew tactical skills adding another board game and a new computer game to the course.

The students’ feedback continues to help us improve the games. Sometimes they’re minor tweaks to the game rules or an additional function to a computer game, sometimes they’re more wide-ranging such as “We didn’t spend long enough playing the game”.

As an instructor, I’m seeing skills develop throughout the course supported by presentations, games and simulator sorties. The students are telling us that they’re benefitting from the games, and their parent units are reporting the difference that the training course gives them.