Afghanistan: History told us what to expect

11/08/2021

As U.S. troops prepare to exit Afghanistan by September 11, 2021, the Taliban has launched a massive offensive across the country, taking over large swathes of territory. This has forced the Afghan government and its security forces to consolidate their power largely in the capital, Kabul, and other major urban areas. As the USA reaches the end of its withdrawal in Afghanistan the conversation has rightly turned to the question of whether it was all worth it in blood and treasure. Winston Churchill wrote in 1948, “Those that fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.” A haunting aphorism when reflecting on Afghanistan.

Since UK operations began in 2003, to the drawdown in 2014, 454 personnel were killed and 298 seriously injured, with 405 of these lives lost in hostile action. The cost of UK operations is more than £8.4 billion. Around 79,000 Afghan Army and Police have been killed in the region. Although it is difficult to establish numbers, the cost of Afghan civilian lives is equally tragic; it is estimated that up to 72,000 have perished. The cost to the United States in terms of lives has been 2,218 US military service personnel killed (1,833 in hostile action) and 20,903 wounded in action. The financial side is rather opaque, $815.7 billion is the 2020 war-fighting operating cost with a total bill for 20 years of war in Afghanistan around $2.26 trillion and counting.

General Sir Nick Carter, Britain’s Chief of Defence Staff, argues that “the international community has built a civil society that has changed the calculus of what kind of popular legitimacy the Taliban want.” He declared the country to be a better place than it was in 2001 and added “the Taliban have become more open-minded.” While that may be the case, the role of kinetic and non-kinetic operations used to mollify the Afghan Taliban towards adopting a more inclusive outlook, 20 years on, remains questionable.

For much of this war, the Taliban were excluded from any solution, except for some covert diplomacy facilitated by third parties. The Commander of the Pakistan 11 Corps in 2010 used the telling metaphor that it was like trying to build a new United Kingdom but excluding the English from the decision process.

The country faces the prospect of an urban enclave surrounded by a diametrically opposed political and military force. As elements of the Afghan National Army (ANA) and allied militias capitulate and join with the Taliban, that organisation also inherits a better trained and equipped force. Inevitably, those aspects that gave tactical advantage to the ANA in the form of US air power and sophisticated surveillance equipment, are missing. The remnants of the ANA’s own air force will also become weakened by a break in the supply chain and reduction in maintenance skills as contractors leave with the American and NATO forces.

We should not be surprised by the situation. There is a horrid predictability to the history of Afghanistan that is told in the loss of lives and depleted political appetite. The three British wars in Afghanistan of 1839, 1878 and 1919; followed by the Soviet-Afghan war of 1979 to 1989 demonstrated that centralised total governance of a geographically difficult and culturally disparate people was not possible without significant and continued investment and assistance. We have seen history repeating itself in Afghanistan.

Afghanistan is home to competing tribes and factions. In his 1924 book Passing it On, General Skeen observed that the Pashtun tribes, and to an extent the other tribes in Afghanistan and the Indian Northwest Frontier, are inherently militant and restless. Over their 5000-year history, the Pashtun tribes have demonstrated one common trait – unity in the face of an external adversary. The arrival of British, Soviet, and later US-led forces has acted to provide a focus. All national powers have found that where they seek to impose control, the warring parties stop fighting each other and concentrate on fighting the invader. They are successful at it. Nations also find that, ultimately, without the investment and imposition of political will, operations in Afghanistan are not sustainable and will lead to retreat.

There is a valid argument that what we see now is not a failure of US and Coalition military strategy and leadership. Rather, it is the result of changes in policy through successive American administrations that required the abandonment of that military strategy.

The mission to deny enemies an ungoverned space was not completed. That mission itself is somewhat of a misnomer. There is government in the country outside of Kabul. But it is one that is fractured, and counter to NATO and allies’ version of stability, decency, and equality.

The BBC reported in April 2021 that Haji Hekmat, the Taliban’s shadow mayor in Balkh District and part of the Taliban in the 1990s, ridicules the ‘Kabul administration’ as corrupt and un-Islamic. The Taliban’s overriding aim has always been to embed Sharia in the country. The legal system which is derived from the Koran, Islam’s central text, and the rulings of Islamic scholars – fatwas, directs Taliban decision making. Whether or not the Taliban would be willing to share power with other Afghan political factions to bring the stability and modernisation desired by NATO and allies, Haji Hekmat defers to the group’s political leadership in Qatar: “Whatever they decide we will accept.”

The prognosis for any remaining NATO influence in Afghanistan is not good. The intelligence community believes Kabul could fall six months after the U.S. withdrawal has finished. Pressed by a resurgent Taliban, the Afghan Government forces are conducting ‘tactical retreat’. The reality is we are witnessing a civil war.

If we are doomed to repeat failures in history as Churchill said, political, military and academic intellect needed to combine to set a framework for success.

- Firstly, it was imperative to have a deeper understanding and recognition of the Taliban mindset. Islam preaches unity, justice and peace, the Taliban were able to tie themselves to religion and to Afghan identity in a way that a government allied with non-Muslim foreign occupiers could not match. Their central tenet of fighting for belief, for janat (heaven) and ghazi (killing infidels) is deeply embedded in the country whereas the Afghan Government is seen as mere US puppetry and the army and police viewed as fighting for financial reward.

- Secondly, and deeply uncomfortable as it may be, any future concept of Afghanistan as a governed space with no havens for fundamental Islamic extremist terrorists needed to include the Taliban. At the very least their leadership. The history of Northern Ireland is a marker for what can be accomplished when opposed sides put aside difference to engage in political discourse.

- Thirdly, any engagement with Afghanistan requires international investment over generations in terms of infrastructure as well as security. If, and this is a big if – the populace of the country wants it, and it is sustainable.

- Fourthly, The Western allies needed a more targeted political policy to win decisively through a focus on al Qaeda and its Taliban allies and denying a safe haven in Pakistan.

- Lastly, the West championed Mosaic warfare. The Taliban defeated the West’s Centre of Gravity – political will – as their ancestors had defeated prior invaders. It begs the question why winning battles does not translate into policy success; Vietnam trailed the answer. As Clausewitz taught us, in war it is the primacy of politics rather than violence that leads to resolution, these concepts Clausewitz brought together in the concept of friction, ‘everything in war is simple, but the simplest thing is difficult.’ The focus on attaining objectives of violence was simple whilst the Taliban focused on objectives of policy.

Had the allies taken the longer-term option to stay and continue ‘as was’, to invest even more in lives and money, perhaps the situation would have eventually been different. But the question would always remain that when Western forces left – as they inevitably would have done, would the country have returned to a similar version of what it was before? History tells us the answer – yes it would and yes it has.

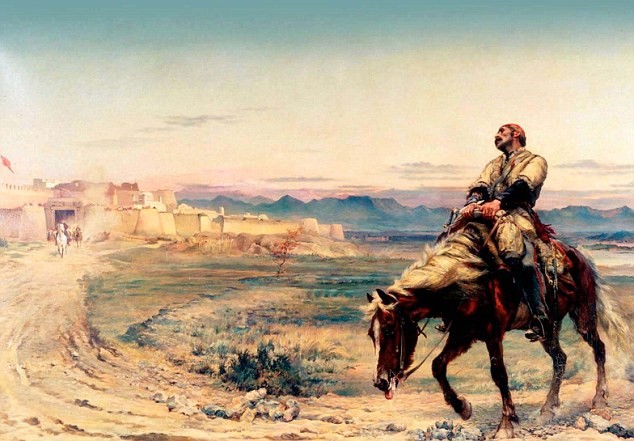

[Feature image: 1879 Elizabeth Thompson, Lady Butler, The remnants of an army, Jellalabad (sic), January 13, 1842.January 13, 1842, Dr William Brydon, the sole survivor of Elphinstone’s army of 20,000 approaches the city of Jalalabad. When a rescue party reached him, they found a shadow of a man, his head sliced open, his tattered uniform heavily bloodstained. When asked ‘Where is the Army?’, Assistant Surgeon William Brydon managed to reply: ‘I am the Army.’]

Categories & Tags:

Leave a comment on this post:

You might also like…

Commonwealth Scholarships play a critical role in developing sustainability and leadership in Africa

Q&A with Evah Mosetlhane, Sustainability MSc, Commonwealth Distance Learning Scholar What inspired you to pursue the Sustainability MSc at Cranfield? I was inspired to pursue the Sustainability MSc at Cranfield because of the university’s ...

How do I reference a thesis… in the NLM style?

You may be including theses within your research. When you do so you need to treat them in the same way as content taken from any other source, by providing both a citation and a ...

Introducing… Bloomberg Trade Flows

Are you interested in world trade flows? Would it be useful to know which nations are your country's major trading partners? If so, the Bloomberg terminal has a rather nifty function where you can view ...

Cranfield alumni voyage to the International Space Station

Seeing our alumni reach the International Space Station (ISS) has a ripple effect that extends far beyond the space sector. For school students questioning whether science is “for them”, for undergraduates weighing their next ...

From classroom to cockpit: What’s next after Cranfield

The Air Transport Management MSc isn’t just about learning theory — it’s about preparing for a career in the aviation industry. Adit shares his dream job, insights from classmates, and advice for prospective students. ...

Setting up a shared group folder in a reference manager

Many of our students are now busy working on their group projects. One easy way to share references amongst a group is to set up group folders in a reference manager like Mendeley or Zotero. ...