Why acting on climate change means we have to de-materialise

09/03/2022

Too much of the debate around climate change and sustainability is fixed on CO2 emissions and renewable energy.

What’s talked about far less, but is equally as fundamental to dealing with the climate emergency — maybe because it’s more problematic, more uncomfortable for all of us as consumers — is our need to de-materialise. In other words, not depending on having so much stuff.

We have to start valuing the things we have and, most of all, start to appreciate the materials involved and how things are actually made. A typical electronic device, one we all have in our homes and rely on, would have needed around four elements from the Periodic Table in the pre-digital age. Now it’s more like 40. Many of those elements will be scarce in term of production levels and have been stripped from multiple natural resources. Often the materials will also have come from nations where working conditions are poor and there are wider problems of conflict and civil unrest. And it’s not just the materials, manufacturing processes mean the use of vast supplies of energy and water. Even the production of data, every single byte of a Tweet, text message or Zoom call, involves the consumption of more energy.

De-materialising, of course, goes against the grain of whole worlds of commercial and consumer imperatives where materials are just commoditised. Societies in developed nations are still based on the ‘pile ‘em high, sell ‘em cheap’ model, accepted as being the blueprint of ‘progress’ and economic success. Scarcity, on the other hand, just means failure. So this is now also the model for developing economies worldwide. Businesses are always looking for growth and to build volumes by reducing costs and prices. In turn this means that we, as consumers, are not careful with materials at the end of their life. They’re disposable. We have to change the traditional economic mindset that preaches how products get cheaper and cheaper as more and more are made. Instead, we need business models that reflect the real value of materials and the cost to the planet. In fact, we probably shouldn’t even be selling products at all — that way business would become more like custodians of the materials they use rather than just their consumers.

The last 10 years has brought changes in attitude and behaviour in the manufacturing sector. In particular, the ‘zero waste to landfill’ principle — but that has largely been driven by legislation. Less waste means lower costs. We need to move forward as a society based on a shared sense of responsibility. Businesses need to manufacture with less, use a smaller bill of materials and be actively looking to simplify their products so they are easier to re-purpose. We all need to be ‘good’ consumers, open to the idea of leasing and sharing rather than straight ownership. In this way the responsibility for end-of-life falls with manufacturers, there are more opportunities for re-use and re-manufacturing of their simpler products. More of the value of the materials stays in the system. We should be making our materials last longer. ‘Cheap’ should only ever be a dirty word.

Circular business models based on re-use of materials are becoming more common. Examples such as Circular Computing (which remanufactures rather than refurbishes laptops) are growing in viability and credibility — recently recognised with a BSI kite mark. But for the moment it’s also the only major player in the remanufactured laptop market. There are some good examples in other markets, like Interface for carpet tiles and Caterpillar for earth moving equipment. But these are still few and far between

For de-materialising to take hold, to be part of the climate emergency era, we need circular enterprises everywhere, in every sector, to help to transform consumer habits and make it easier for us to make better choices. Business should be jostling to make good use of all the kinds of materials that we would normally just throw away.

Categories & Tags:

Leave a comment on this post:

You might also like…

Keren Tuv: My Cranfield experience studying Renewable Energy

Hello, my name is Keren, I am from London, UK, and I am studying Renewable Energy MSc. My journey to discovering Cranfield University began when I first decided to return to academia to pursue ...

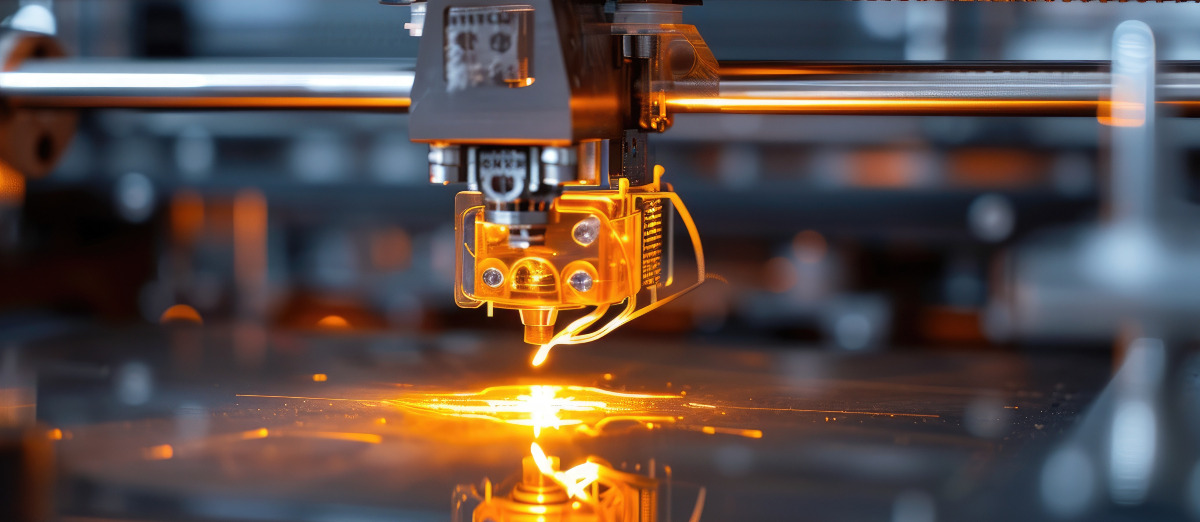

3D Metal Manufacturing in space: A look into the future

David Rico Sierra, Research Fellow in Additive Manufacturing, was recently involved in an exciting project to manufacture parts using 3D printers in space. Here he reflects on his time working with Airbus in Toulouse… ...

A Legacy of Courage: From India to Britain, Three Generations Find Their Home

My story begins with my grandfather, who plucked up the courage to travel aboard at the age of 22 and start a new life in the UK. I don’t think he would have thought that ...

Cranfield to JLR: mastering mechatronics for a dream career

My name is Jerin Tom, and in 2023 I graduated from Cranfield with an MSc in Automotive Mechatronics. Originally from India, I've always been fascinated by the world of automobiles. Why Cranfield and the ...

Bringing the vision of advanced air mobility closer to reality

Experts at Cranfield University led by Professor Antonios Tsourdos, Head of the Autonomous and Cyber-Physical Systems Centre, are part of the Air Mobility Ecosystem Consortium (AMEC), which aims to demonstrate the commercial and operational ...

Using grey literature in your research: A short guide

As you research and write your thesis, you might come across, or be looking for, ‘grey literature’. This is quite simply material that is either unpublished, or published but not in a commercial form. Types ...