New modular manufacturing process for latex rubber gloves on course for net zero

26/11/2021

In 2019 the average medical gloves used in England every month was 150 million. During the height of the pandemic (Feb 2020 – August 2021), this figure rose to 500 million. To put it into context, that’s an entire football pitch packed 1.6m high with used gloves…. every single month in England alone. When we look at the world, this totals around 70 billion gloves per month.

Last year, we shared how research led by Cranfield’s Professor Krzysztof Koziol, in partnership with Malaysian medical glove manufacturer, Meditech Gloves, was paving the way for a sustainable future for the degradable glove industry, as well as supporting the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. (Read the article here).

Traditional methods of bulk dipping to produce rubber gloves at scale have not been changed for decades and they may not be considered sustainable, causing huge concern against the backdrop of global net zero ambitions.

Existing factories are optimised for mass production and focusing on synthetic rubber, using heavy petrochemical sources, generating a considerable amount of waste, and releasing CO2 into the atmosphere. Due to a centralised production, another challenge is the CO2 emission coming from extensive global shipment of the final product.

If you consider a box of synthetic gloves, every single element, including the raw rubber material, is man-made, and with it, comes the associated carbon footprint. In comparison, natural rubber, produced by the rubber tree, mostly cultivated in South East Asia, is fed by the CO2 in the atmosphere, the energy from the sun and water from the ground. In this approach we can balance the carbon emissions in each of the manufacturing processes to achieve a truly sustainable operation in partnership with the natural environment.

Professor Koziol and his research team, including PHD student, Eva Pelaez Alvarez, are now building on their work, looking at new manufacturing approaches for natural latex rubber gloves as well as promoting alternative sources for natural rubber. No-one else in the world right now is doing this. Cranfield is leading the way, and this is just the start.

New modular manufacturing method

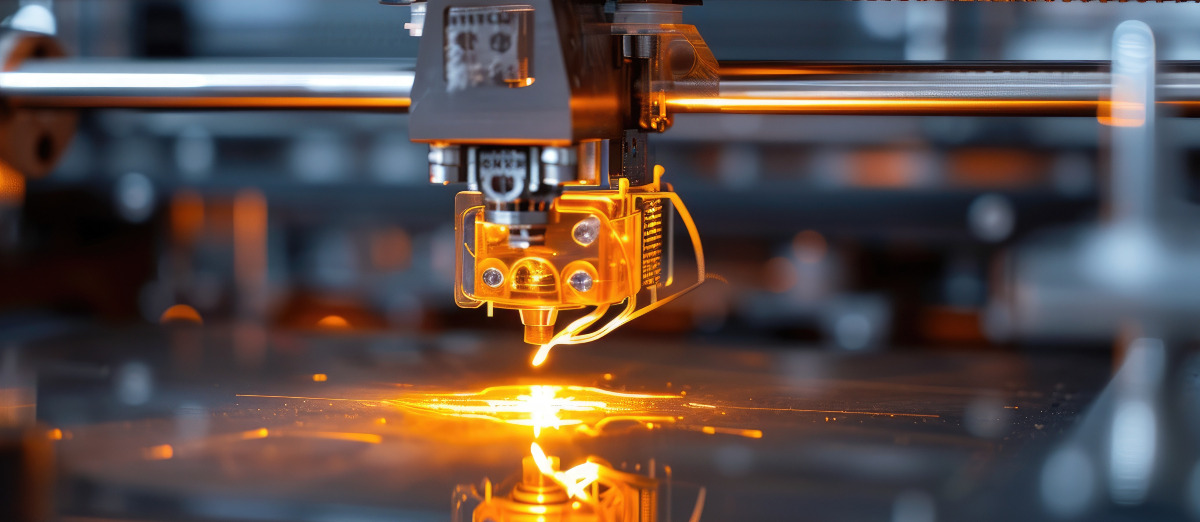

Large scale production of rubber gloves is currently accomplished by the dipping method, where moulds that mimic the shape of hands (formers) are submerged into a liquid compounded latex, creating a film that is later vulcanised.

A significant discovery for the industry, the Cranfield team has now created a new 3D printing process for making rubber structures from latex. 3D printing is a technology that is increasingly being used at scale by large industry. It is a process of joining materials layer upon layer to make parts. Among its advantages is customisation, reduction of waste and the possibility of creating complex layered structures. However, the use of elastomers in 3D printing is still quite limited, especially for the creation of thin elastomeric film structures such as gloves. Moreover, little progress has been made in the use of natural rubber latex for 3D printing.

In order to transfer the process on a scale production, a novel in-house 3D printer has been developed by Cranfield, paving the way for the future manufacturing of gloves to create low cost, sustainable, raw material saving and customised latex gloves.

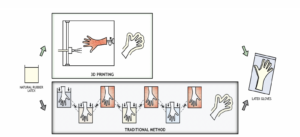

Concept diagram of the new Cranfield 3D printing technology versus the traditional glove manufacturing method

This is a new modular method of manufacturing rubber gloves, representing a future for decentralised portable and energy efficient factories. Furthermore, these can be deployed closer to the end user (eg. medical facilities) to avoid extensive transportation and related CO2 footprint.

The novel Cranfield technology delivers ten times the production capacity of traditional methods. The same factory can be ten times smaller, offering immediate energy savings in production; less space, less concrete and heating required, improving the resilience and flexibility of the entire supply chain.

Alternatives natural sources

The natural latex used to produce the gloves is derived from the rubber tree, a plant only grown in a tropical climate. There is an ambition to source and grow natural alternatives for latex closer to the end users. With no commercially viable native sources in the USA or Europe, there are inevitable carbon emissions associated with transportation of the rubber to our shores. However, by researching how to scale up and extract latex efficiently from the local plants in Europe, the industry will open up decentralised production opportunities of gloves. This would not only transform the glove market’s sustainability but have positive effects for other major industries as well, including the rubber tyre industry.

Better than Net ZERO?

The carbon capture is a major part of the natural latex production. If possible we should aim to use this material as a feedstock for any suitable rubber production processes. This could significantly transform the rubber industry. If reduction of the synthetic latex production in favour of natural rubber was possible, the rubber products will have an immediate positive effect on carbon output. Even if we are not quite at the stage of developing an alternative source of natural latex, and we continue to use tankers packed full of natural latex, produced from CO2 in the atmosphere, we can achieve net zero. The potential to produce natural latex locally from alternative sources is the next step. Improving the rubber gloves manufacturing process, will have a further impact on the reduction of CO2 mission. The Cranfield technology is an example of how this could be done in the future.

The holy grail would be to achieve sustainable manufacturing production, together with producing the natural latex closer to the end users – and this would make natural latex rubber gloves production ‘EVEN Better than Net ZERO’. And that breakthrough would be a game changer, transforming the entire rubber industry and with it, starting to win the race to net zero carbon.

Categories & Tags:

Leave a comment on this post:

You might also like…

Keren Tuv: My Cranfield experience studying Renewable Energy

Hello, my name is Keren, I am from London, UK, and I am studying Renewable Energy MSc. My journey to discovering Cranfield University began when I first decided to return to academia to pursue ...

3D Metal Manufacturing in space: A look into the future

David Rico Sierra, Research Fellow in Additive Manufacturing, was recently involved in an exciting project to manufacture parts using 3D printers in space. Here he reflects on his time working with Airbus in Toulouse… ...

A Legacy of Courage: From India to Britain, Three Generations Find Their Home

My story begins with my grandfather, who plucked up the courage to travel aboard at the age of 22 and start a new life in the UK. I don’t think he would have thought that ...

Cranfield to JLR: mastering mechatronics for a dream career

My name is Jerin Tom, and in 2023 I graduated from Cranfield with an MSc in Automotive Mechatronics. Originally from India, I've always been fascinated by the world of automobiles. Why Cranfield and the ...

Bringing the vision of advanced air mobility closer to reality

Experts at Cranfield University led by Professor Antonios Tsourdos, Head of the Autonomous and Cyber-Physical Systems Centre, are part of the Air Mobility Ecosystem Consortium (AMEC), which aims to demonstrate the commercial and operational ...

Using grey literature in your research: A short guide

As you research and write your thesis, you might come across, or be looking for, ‘grey literature’. This is quite simply material that is either unpublished, or published but not in a commercial form. Types ...