Why we need to tackle climate change and the sixth mass extinction at the same time

17/11/2021

COP26 necessarily has a major focus on reducing, eliminating, and sequestering carbon. Less prominent in the headlines is the crisis in biodiversity – the Sixth Great Extinction, with the current rate of species loss to be as much as 1 000 times higher than the natural background – caused by us. We have been losing species by habitat loss, unchecked invasive species, overexploitation (extreme hunting and fishing pressure), pollution, and climate change. The UK itself is in the bottom 10% of biodiversity as a country – with about half of its biodiversity left – compared to the global average of 75%, which itself is nothing to celebrate.

This cannot be placed on the back burner, we can’t get to it after we have tackled carbon reduction, it is imperative that we tackle it at the same time as the same problem – Planetary system degradation caused by Humanity. If we don’t, it can result in perverse outcomes. For example, the EU Directive on Biofuels for transport (2003) was aimed at increasing the proportion of biofuels available for vehicles in Member States. Unfortunately, in order to satisfy this requirement, the primary tropical rainforest was cleared on a vast scale to produce palm oil for biofuels – the wrong trees in the wrong place. If we simply focus on plants solely being means of sequestering carbon in their mass and soils, we could be making an even bigger mistake.

Internationally nature and its contribution to people and society (NCP) is being increasingly recognised, going beyond Natural Capital and Ecosystem Services, which can come across to some as living from nature, rather than living in nature. It must be said the Ecosystem Service approach, which has highlighted just how society is utterly dependent on nature, has been both compelling and fruitful in the science, policy and practice arenas. Critically, it made Finance Ministries the world over sit up and take notice. We have the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) responsible for advancing knowledge on human-induced climate change, and the UN Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) is an intergovernmental organization established to improve the interface between science and policy on issues of biodiversity and ecosystem services, separately.

So why is tackling biodiversity loss and net-zero (and negative) carbon together essential? Nature not only has those compositional attributes that we are familiar with – charismatic animals, mature forests, and beautiful landscapes but there is a lot going on in a mature functioning system, which is more than the sum of its parts, including the deep spiritual meaning and use that nature has for Indigenous communities and the biophilia that we all benefit from. Three-quarters of the land-based environment and about two-thirds of the marine environment have been significantly transformed by human actions, and even in “pristine” areas, we can detect microplastics brought there on the wind. On average these trends have been less severe or avoided in areas held or managed by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities.

We know that complex, functioning ecosystems, with intact trophic webs – plants, herbivores, predators, decomposers and detritivores – produce emergent, dynamic properties, such as resilience. These dynamic properties begin to emerge as ecosystems go through the process of succession from primary colonisers, such as lichen, through hardy plants, to grass, shrubs and tree dominated systems or wetlands – accompanied by the arrival of all the other living components of these ecosystems. Crucially, it is the interaction of these species, through predation, symbiosis and decomposition that allows the system to respond to changes, sudden or gradual, in environmental conditions. By keeping systems in a simple, immature, state through land transformation, we stop those feedbacks which have effects beyond their immediate locality, and to the global ecosystem – Gaia – contributing, for example, to cloud cover in response to warming. What is more, when there are more species these system-level responses are greater – for example, more plant biomass produced, and greater tolerance to drought. This increase in biomass is critical to capturing carbon dioxide – and there is more captured by a complex ecosystem, such as a tropical forest, or peatland, than by a monoculture of trees – along with gains in biodiversity and ecosystem function.

In other words, increased connected biodiversity leads to increased function and connected resilience – planting the right trees in the right place is a must if we are to increase ecosystem complexity, function, and resilience. Tropical forests are so complex that planting key species may also be problematical – animal restructuring of communities. This is why restoring ecosystems in a holistic way is essential to maximising carbon capture, as will maximising biodiversity in agricultural systems – here agroforestry, inter-and mixed-cropping, permaculture – all “mimicking nature” will help with maximising yield and minimising inputs.

This isn’t a new idea. St Thomas Aquinas wrote, in the 13th Century “It is better to have a multiplicity of species than a multiplicity of individuals”, and Darwin recognised the effect of growing more than one species together in an experimental plot in the 19th Century. However, we do not know the complete composition of complex ecosystems and losing a critical species may cause the whole system to collapse. We do not know which species are the “rivet” whose loss causes the whole system to fall apart. To quote another philosopher, Joni Mitchell, “Don’t it always seem to go, that you don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone”.

By considering Net Zero and Biodiversity Loss as the same problem, our solutions will be far more impactful, and ethically sound. Whilst we are about it, we should consider a much closer relationship between IPCC and IPBES – if not an actual merger.

Let’s stop losing the parts to protect and restore the whole, and reconnect Nature and Culture.

Categories & Tags:

Leave a comment on this post:

You might also like…

Keren Tuv: My Cranfield experience studying Renewable Energy

Hello, my name is Keren, I am from London, UK, and I am studying Renewable Energy MSc. My journey to discovering Cranfield University began when I first decided to return to academia to pursue ...

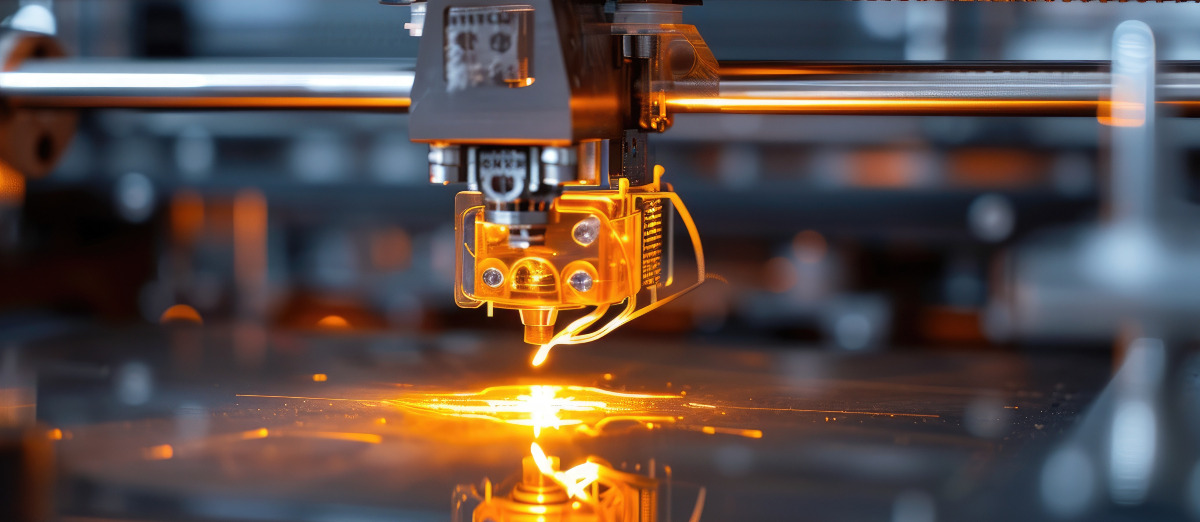

3D Metal Manufacturing in space: A look into the future

David Rico Sierra, Research Fellow in Additive Manufacturing, was recently involved in an exciting project to manufacture parts using 3D printers in space. Here he reflects on his time working with Airbus in Toulouse… ...

A Legacy of Courage: From India to Britain, Three Generations Find Their Home

My story begins with my grandfather, who plucked up the courage to travel aboard at the age of 22 and start a new life in the UK. I don’t think he would have thought that ...

Cranfield to JLR: mastering mechatronics for a dream career

My name is Jerin Tom, and in 2023 I graduated from Cranfield with an MSc in Automotive Mechatronics. Originally from India, I've always been fascinated by the world of automobiles. Why Cranfield and the ...

Bringing the vision of advanced air mobility closer to reality

Experts at Cranfield University led by Professor Antonios Tsourdos, Head of the Autonomous and Cyber-Physical Systems Centre, are part of the Air Mobility Ecosystem Consortium (AMEC), which aims to demonstrate the commercial and operational ...

Using grey literature in your research: A short guide

As you research and write your thesis, you might come across, or be looking for, ‘grey literature’. This is quite simply material that is either unpublished, or published but not in a commercial form. Types ...