A sit down with Neil Harris

07/08/2019

Controlling our climate

We sat down with Neil to find out more about his experience in atmospheric science and his involvement in the Montreal Protocol, one of the only international agreements to be ratified by all United Nation member states.

Tell us about the Centre for Environment and Agricultural Informatics

“I came to Cranfield three years ago to set up, lead and develop research and teaching on the atmospheric implications of what is currently going on at Cranfield. So we’re really trying to work with everyone across the university that is relevant to the work that is ongoing. We collaborate with other environmental researchers (e.g. on remote sensing, land use and on biodiversity in CEAI)”.

How did you become a professor in atmospheric science?

“I did my chemistry degree at Oxford University, and there you do three years of coursework which didn’t really get me buzzing, and then the whole of the last year is research only which was fantastic. The final year was on work related to stratospheric ozone. I was amazed at the fact that you could put in one in a part per million-million levels of a compound into the atmosphere, and it could cause major damage. I wanted to know how so molecules can have such a global effect.

I did my PhD at the University of California with a guy called Sherwood Roland, who originally put forward the idea that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) could deplete ozone, and later won a Nobel Prize for it. After I had been there a year doing the mandatory coursework, he gave me a load of measurements of ozone and said ‘analyse them, we want to know if there is a trend in the northern hemisphere’, because by that stage it was known there was a huge ozone hole over the Antarctic, but we didn’t know what was happening locally. So I was lucky I had an improved version of the data made for me to use, and I was able to do that analysis during my PhD. I was in the right place at the right time to become involved in the Montreal Protocol’s assessment process, co-authoring the chapters on the analysis of ground based data while still a graduate student.”

What is the Montreal Protocol?

“The Montreal protocol is the international legislation or the international framework which was set up in the mid-1980s to control the emissions of the chemicals which depleted ozone. It is currently signed and ratified by 197 countries. It’s a framework where academics, government, industry, NGOs all can get together and make progress on limiting emissions. Over time, the control on limiting emissions and other gases has increased as a result of improvements in engineering, so it’s been immensely successful.”

What is your involvement in the Montreal Protocol and what are some of the impacts it has had?

“A key part of the Montreal Protocol is that there are assessments every four years, where the latest science and technology is reviewed and options are given as to what further measures could make a difference. I am still involved in the review process every four years. I was awarded the Natural Environment Research Council inaugural International Impact Award and the Overall Impact Award for my role in the successful development of the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer.

The measures are making a difference in different ways – not just reducing ozone depletion. Most recently, hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), which are much stronger greenhouse gases than carbon dioxide, were controlled as well. Overall the Montreal Protocol will have saved half to three-quarters of a degree of warming, which equates to about 10-15 years of CO2 emissions saved. This is more than any international treaty on climate change.”

What influenced your move to Cranfield in 2016?

“I’ve always thought it is important that academics should not simply wave red cards at people or just say ‘here’s a problem’ because if they don’t engage, the solutions will be reached much slower. There’s always been quite close links between the academic community and government, but not necessarily with industry, and what the experience with the Montreal Protocol showed was that if you have good working relationships with industry, they better understand what the problem is and where to put their efforts in most. Thirty years ago the evidence for taking action on climate change was as strong as it was for ozone depletion – but we have done so little about it. Working across our areas of expertise at Cranfield, whether that is agriculture or aviation, is a good opportunity to try and work closely with experts who know all about the processes leading to the emissions”.

Why is it important to continue to study atmospheric science, and why particularly across our areas of expertise at Cranfield?

“In addition to ozone depletion and climate change, air quality is a massive problem. According to the World Health Organisation, air pollution is killing 7 million people a year. It is a really complicated problem from all angles and we need the input from atmospheric scientists as well as other sectors such as car manufacturers, health experts and governments. What we don’t know well enough is how to give good advice on mitigation and what measures to take. For example, if we had a billion pounds to spend on flood defence in the UK, we would not know where to spend it. Good response will require a good understanding of all aspects of the problem. So there is still a lot of improvement needed, and it’s just fun!

When people leave Cranfield, they understand the impacts of where they are going to work, we want them to be knowledgeable about what the impact of their role has on the climate, etc. Even management students should learn about sustainability issues, because it’s about getting people knowledgeable into positions where decisions are made. Cranfield must continue to use its links with government and industry. Being an applied research university, Cranfield has a special role in tackling these issues. It’s just so important that we don’t end up with our advice in bunkers, we should be telling government, we should be talking to industry, talking to schools in order to make a difference”.

Neil Harris was appointed Professor of Atmospheric Informatics in 2016. Neil has extensive experience in the international coordination of atmospheric research and ensuring that the understanding gained is transferred to the policy and public fields. With expertise on issues related to stratospheric ozone depletion, climate change and air quality, Neil has given, and continues to give expert advice to policy makers around the world.

Categories & Tags:

Leave a comment on this post:

You might also like…

Keren Tuv: My Cranfield experience studying Renewable Energy

Hello, my name is Keren, I am from London, UK, and I am studying Renewable Energy MSc. My journey to discovering Cranfield University began when I first decided to return to academia to pursue ...

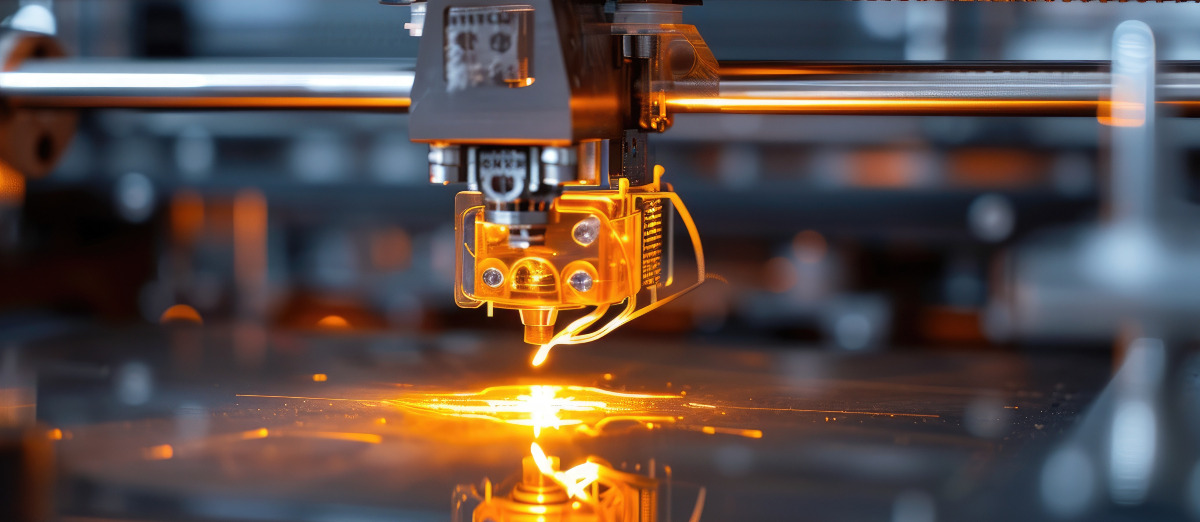

3D Metal Manufacturing in space: A look into the future

David Rico Sierra, Research Fellow in Additive Manufacturing, was recently involved in an exciting project to manufacture parts using 3D printers in space. Here he reflects on his time working with Airbus in Toulouse… ...

A Legacy of Courage: From India to Britain, Three Generations Find Their Home

My story begins with my grandfather, who plucked up the courage to travel aboard at the age of 22 and start a new life in the UK. I don’t think he would have thought that ...

Cranfield to JLR: mastering mechatronics for a dream career

My name is Jerin Tom, and in 2023 I graduated from Cranfield with an MSc in Automotive Mechatronics. Originally from India, I've always been fascinated by the world of automobiles. Why Cranfield and the ...

Bringing the vision of advanced air mobility closer to reality

Experts at Cranfield University led by Professor Antonios Tsourdos, Head of the Autonomous and Cyber-Physical Systems Centre, are part of the Air Mobility Ecosystem Consortium (AMEC), which aims to demonstrate the commercial and operational ...

Using grey literature in your research: A short guide

As you research and write your thesis, you might come across, or be looking for, ‘grey literature’. This is quite simply material that is either unpublished, or published but not in a commercial form. Types ...