Anxiety: Sharing a diagnosis at work

02/08/2023

The biggest dread I had when I told my colleagues that I have Generalised Anxiety Disorder was that they would take work away from me – that the immediate assumption would be that I cannot cope and that the answer to that would be to remove workload.

That is not to say that reducing workload is not an answer; it sometimes is – but there is a world of difference between having work taken away and asking for the workload to be reduced. The first can increase anxiety and the latter help alleviate it. My experience of sharing was a good one but for some, it is not.

Fear of a ‘knee-jerk reaction’ is a term that is most frequently used to me in conversations about sharing disabilities. It is often an unworthy term to use. It suggests a lack of care or thought and that may not be the case. Despite how they may come across, the reactions of people can be well-intentioned but clumsy and sit at the forefront of the wish to help someone who shares in relation to a condition or mental well-being.

Sharing can be received with a sense of dread by some people. It is quite a natural human reaction that a line manager is going to immediately think about how it affects them. Perhaps they are very busy and stressed and it is interpreted as a burden that may affect their own mental health. Perhaps they worry about how they are meant to deal with the news or maybe they feel discomfort by it.

The key to it all is communication – no great surprise there. A mature conversation needs to take place to understand how any sharing of mental health or neurodiversity affects everyone.

The first thing leaders should be thinking about is the support they should provide to the person telling them about a condition. It may have taken a great deal of thought and agonising over time for someone to reach a point where they are able to tell others about a diagnosis or how they are feeling. There is a mass of stereotypes, labels, negative tropes, and convenient but ill-fitting boxes that people fear being associated with.

People sharing a condition may be concerned about how they are viewed – some people embrace their diagnosis and take ownership of it. Others may feel embarrassed or worried. They may be asking themselves how it is going to affect their progression – will that promotion they recently got be taken away, will it be reviewed, will nothing change, will everything change? These thoughts will race and do so accompanied by worry.

A good leader will engage in questions of workplace adjustment and workload, yes; but they will also take steps toward education and make sure that the team does too. Reading articles or watching videos in conjunction with actively listening to the person sharing can be an immense help. The leader and staff may book specific training courses to ensure they are better informed.

One of the great battles that are being fought by many people is the ‘normalisation’ of neurodiversity and mental health conditions. That is not to say that the complexities and methods of addressing them should be ignored – it is more about realising the beauty, wonder, and invention that is present in humanity. Accepting that being ‘typical’ is actually the exception.

Let’s return to anxiety… It often sits outside of discussions on neurodiversity but in conversations, I find more people including it (not least because it often appears as comorbidity with other aspects of neurodiversity).

Armstrong (2010) offers a positive outlook on anxiety by describing it as a virtue, especially in regard to the intellectual and artistic creative process. Anxiety can provide motivation, with many finding advantages in roles that require focus, sharpness, observation, and wit. Those with anxiety can be great reflectors, taking advantage of their tendency to ‘consider’ and propose improvements or innovation. Reflection does not necessarily mean taking a long time – it is a skill that can be honed. None of this ignores that there can be ‘downsides’ to anxiety; those that have anxiety are well aware of them and so is science.

What this small commentary aims to do is encourage leaders, line managers, and co-workers to improve their understanding of anxiety not in terms of what is negative about it, but what is positive. Strive to be ambassadors in this and other aspects of mental health, disability, and neurodiversity in breaking down the unhelpful and outdated wall of ‘typical’ and helping realign society in terms of equity.

Categories & Tags:

Leave a comment on this post:

You might also like…

Keren Tuv: My Cranfield experience studying Renewable Energy

Hello, my name is Keren, I am from London, UK, and I am studying Renewable Energy MSc. My journey to discovering Cranfield University began when I first decided to return to academia to pursue ...

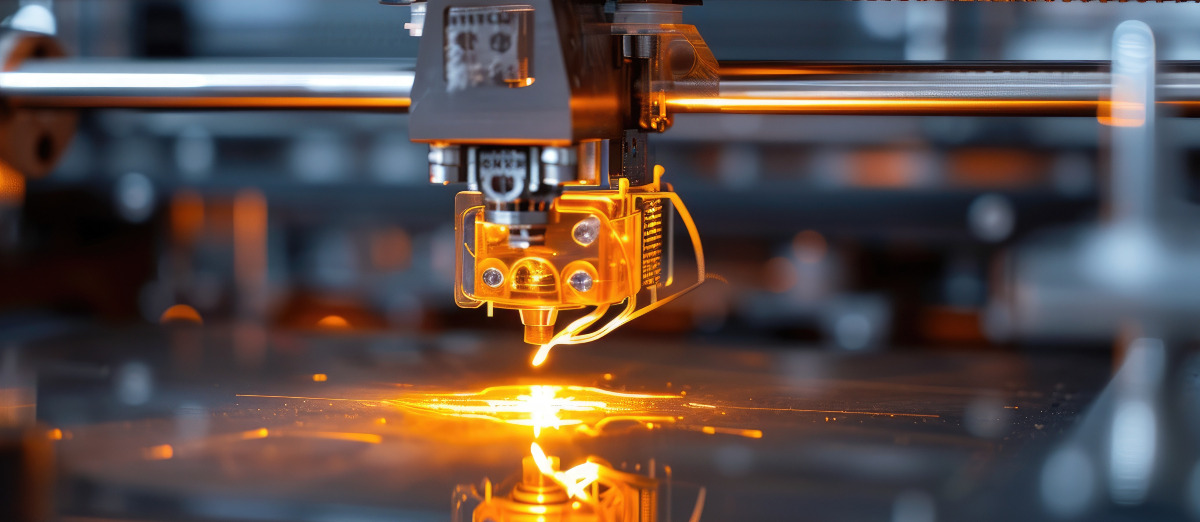

3D Metal Manufacturing in space: A look into the future

David Rico Sierra, Research Fellow in Additive Manufacturing, was recently involved in an exciting project to manufacture parts using 3D printers in space. Here he reflects on his time working with Airbus in Toulouse… ...

A Legacy of Courage: From India to Britain, Three Generations Find Their Home

My story begins with my grandfather, who plucked up the courage to travel aboard at the age of 22 and start a new life in the UK. I don’t think he would have thought that ...

Cranfield to JLR: mastering mechatronics for a dream career

My name is Jerin Tom, and in 2023 I graduated from Cranfield with an MSc in Automotive Mechatronics. Originally from India, I've always been fascinated by the world of automobiles. Why Cranfield and the ...

Bringing the vision of advanced air mobility closer to reality

Experts at Cranfield University led by Professor Antonios Tsourdos, Head of the Autonomous and Cyber-Physical Systems Centre, are part of the Air Mobility Ecosystem Consortium (AMEC), which aims to demonstrate the commercial and operational ...

Using grey literature in your research: A short guide

As you research and write your thesis, you might come across, or be looking for, ‘grey literature’. This is quite simply material that is either unpublished, or published but not in a commercial form. Types ...