The health of ransomware

15/05/2017

Last week’s cyber attacks on the NHS, and across the world, were the latest in a long line of ransomware attacks, something that is fast becoming one of the most common cyber threats on the Internet. Ransomware is the name given to a class of cyber attacks that encrypt the files on a victim’s computer. The ransomware will then demand a payment from the victim in order to decrypt the files, essentially holding the victim’s data to ransom. Traditionally, these attacks have targeted documents, photos, and videos, on the victim’s machine and, while the malware doesn’t remove the files from the device entirely, the encryption is so strong that they are effectively inaccessible. However, if the ransom is paid the victim is given a decryption key and, in turn, access to all of their files.

One of the most attractive things about ransomware is that it effectively bypasses a number of the problems faced by cybercriminals, for example, the black market for stolen credit cards has largely collapsed. Therefore, generating tangible real-world value from cyber attacks is becoming increasingly difficult. As our economy becomes more focused on information and indeed our own daily lives become more information-dependent, then it is no surprise that we now place such a high price on our own information. What price would you put on your photos of your children growing up or what price would an organisation place on its key documents? Of course, it would be possible for a cyber criminal to sell this information to a competitor, but that would involve a lot of complicated interactions and a risk to the anonymity of the criminal.

How do the cyber criminals extract money?

Ransomware only needs a connection between the victim and the distributor of the ransomware. There is no requirement for trusted go-betweens, hence the appeal of this malware for cyber criminals. One of the keys to enabling this form is crime is the ability for attackers to receive money but still remain ‘anonymous’, for most ransomware this is through Bitcoin. Bitcoin is an entirely digital currency that I’ve talked about before on this Cranfield blog. Whilst it is anonymous (in that accounts can’t be tied to individuals) it is public in that it is possible to see every transaction. In fact, there are several wallets associated with particular variants of ransomware that contain over £5 million worth of Bitcoins.

The last year has seen ransomware authors become increasingly inventive. For example, they have begun to move to target a wide range of devices including smartphones, tablets and internet-connected TVs. There have even been demonstrations of ransomware targeting the systems used to run machinery in factories and power plants. As holding personal photos and videos to ransom is a very emotive attack it is also not surprising that this human element has been preyed upon. For example, the ‘PopcornTime’ malware will decrypt your files for free if you infect two other people with the ransomware and convince them to pay – a clearly well thought out game-theory tactic.

The piece of malware that has resulted in significant compromises within the NHS, amongst other large networks, is named WannaCry or WannaCrypt and has two main phases to the attack: an initial exploit (that ‘breaks into’ the computer) and the ‘payload’ that performs the encryption and manages the victims’ experience. This includes notifying the victim of the infection, payment and then decryption. Interestingly, the initial exploit is from a set of NSA (National Security Agency) tools that were leaked by the ‘Shadow Brokers’ group. This exploit has been copied from these tools, designed for national security applications, and repurposed for criminal activity.

Why can’t the authorities stop this?

Before laying the blame at the NSA’s door it is also important to understand that when these hacking tools were leaked, Microsoft looked at the tools and created an update for Windows that effectively rendered this exploit ineffective. This update was published in March with a Critical status indicating the severity and importance of applying this update. In September last year, both Microsoft and US-CERT strongly recommended upgrading the version of the filesharing that this exploit targets, again following this advice would mean that the attack was ineffective.

Victims of this cyber attack are potentially ignoring the advice of US-CERT and Microsoft from over eight months ago, have not applied critical updates that were released two months ago or are still using Windows XP, a version that reached end-of-life support from Microsoft in April 2014.

It has become apparent that a kill switch has been found that stops the spread of this infection, this is essentially a way of turning off the malware. Before spreading itself, the ransomware checks whether a particular website exists, if it does then the malware does not run. A researcher found mention of this website within the code for the malware and purchased it – inadvertently stopping the spread of the ransomware. This is too late for those already infected but should buy some time to allow those who are not up to date to install the critical software patches from two months ago.

How to stay protect yourself from a cyber attack

Ransomware is not going to go away and most analysts believe it is only going to increase, so it is important to protect yourself. Luckily most ransomware can be prevented by employing basic cyber hygiene: run an anti-virus software, update your operating system and applications (yes, this includes Adobe PDF reader and Microsoft Office!), regularly back-up your files and be careful with links sent in emails. This simple advice will help you deal with the majority of threats you are likely to face. If you are an organisation consider the NCSC’s advice with guidance such as the 10 Steps to Cyber Security or Cyber Essentials. Whilse these won’t protect you against all possible threats, if you followed this advice you would not be vulnerable to this WannaCry attack.

If you are a victim of ransomware, the standard advice is do not pay – this can be a difficult decision to make particularly as the malware often involves a countdown timer designed to make the victim nervous and force a rushed decision. The NoMoreRansom initiative provides a number of decrypters for particular ransomware variants so you may be able to decrypt your files without paying the criminal.

Dr Duncan Hodges and Dr Oliver Buckley, Information Operations Group, Centre for Electronic Warfare, Information and Cyber, Cranfield Defence and Security

Categories & Tags:

Leave a comment on this post:

You might also like…

Keren Tuv: My Cranfield experience studying Renewable Energy

Hello, my name is Keren, I am from London, UK, and I am studying Renewable Energy MSc. My journey to discovering Cranfield University began when I first decided to return to academia to pursue ...

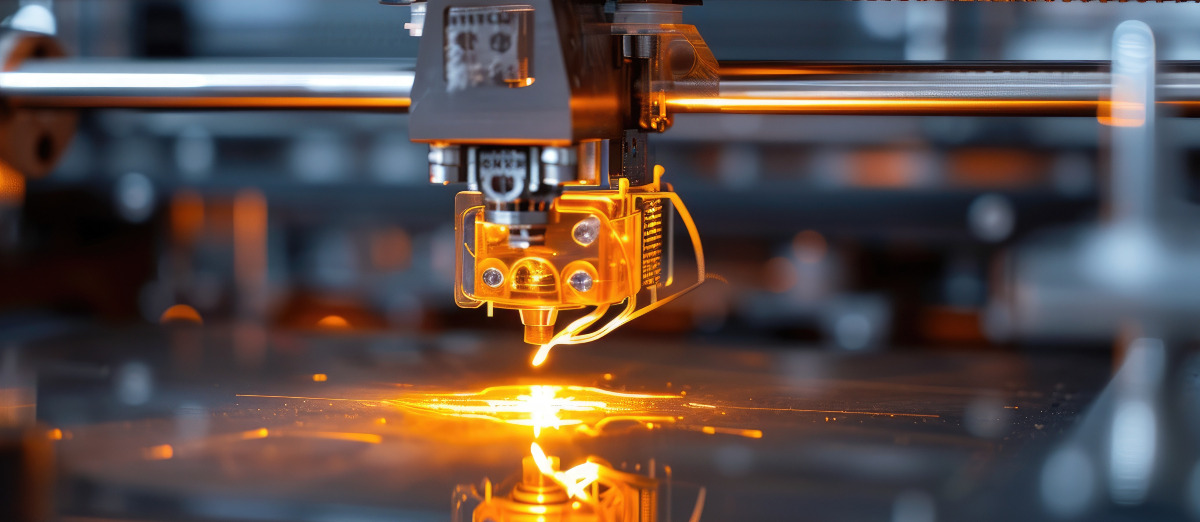

3D Metal Manufacturing in space: A look into the future

David Rico Sierra, Research Fellow in Additive Manufacturing, was recently involved in an exciting project to manufacture parts using 3D printers in space. Here he reflects on his time working with Airbus in Toulouse… ...

A Legacy of Courage: From India to Britain, Three Generations Find Their Home

My story begins with my grandfather, who plucked up the courage to travel aboard at the age of 22 and start a new life in the UK. I don’t think he would have thought that ...

Cranfield to JLR: mastering mechatronics for a dream career

My name is Jerin Tom, and in 2023 I graduated from Cranfield with an MSc in Automotive Mechatronics. Originally from India, I've always been fascinated by the world of automobiles. Why Cranfield and the ...

Bringing the vision of advanced air mobility closer to reality

Experts at Cranfield University led by Professor Antonios Tsourdos, Head of the Autonomous and Cyber-Physical Systems Centre, are part of the Air Mobility Ecosystem Consortium (AMEC), which aims to demonstrate the commercial and operational ...

Using grey literature in your research: A short guide

As you research and write your thesis, you might come across, or be looking for, ‘grey literature’. This is quite simply material that is either unpublished, or published but not in a commercial form. Types ...