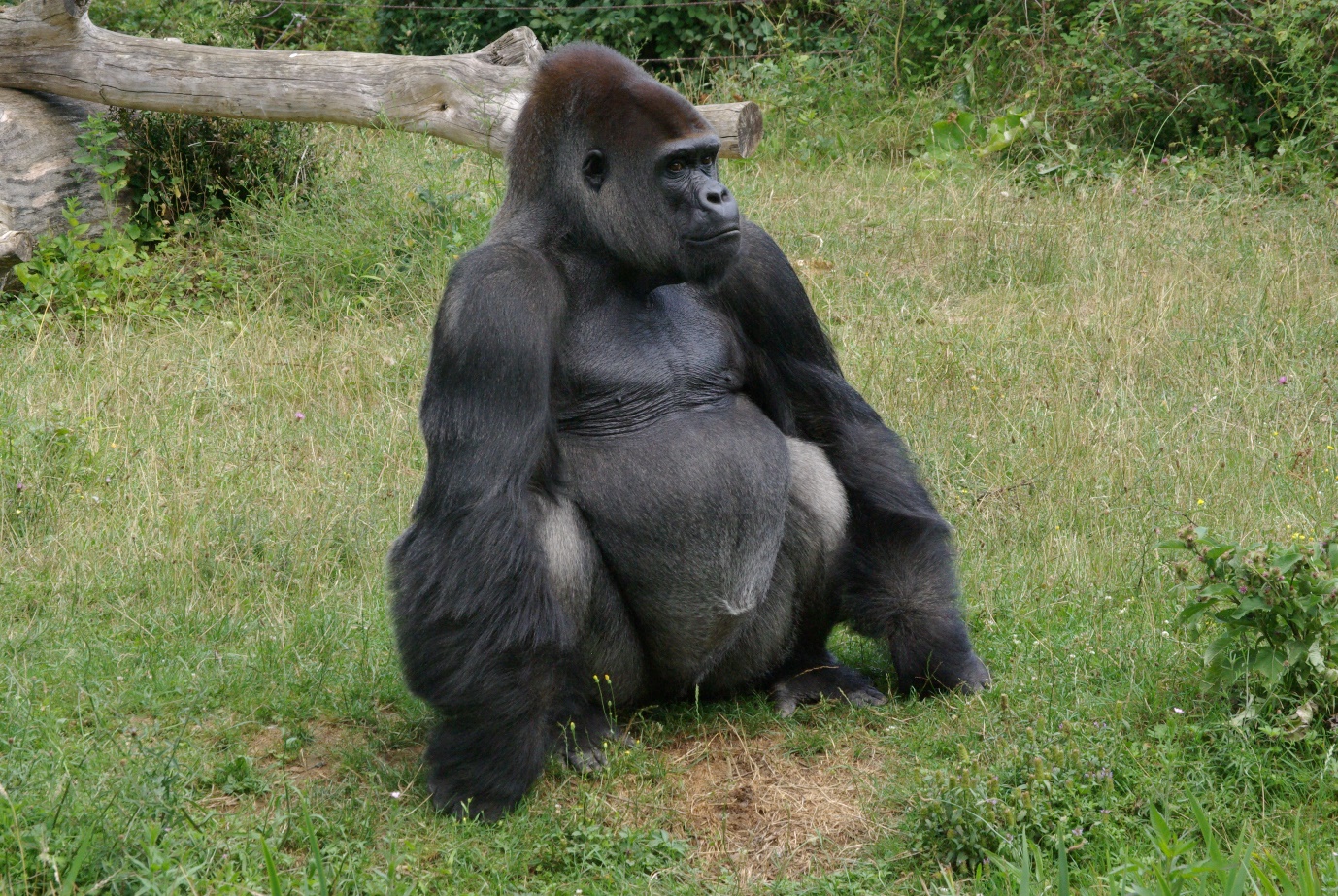

Gorilla Management

26/07/2017

This fine fellow lives in La Vallée des Singes (the Valley of the Apes) in Vienne, France, where Pippa and I spent a wonderful day visiting the different apes and monkeys. But his presence reminded me of a conversation I had some time ago about Gorilla Management when running a programme in the Gambia.

So what is Gorilla Management?

Well, you have all probably heard of Gorilla Gardening. This is where an individual or group of people take over a piece of land which is not their own and improve it through planting flowers, shrubs etc. There are Gorilla burials too.

Gorilla Management is exactly the same — it is where an individual or group of individuals usurp enough power to take over the management of part of the business or the whole business, with the intention of improving it.

So you probably think that this isn’t possible in business. Yes it is! I will tell you some stories about how this has been done and then talk about a few principles that I think you should apply before you consider doing this yourself.

I have seen Gorilla Management practised, and practised it myself when I worked for Unilever (which was some time ago, so hopefully I won’t embarrass too many people). But the best case of Gorilla Management I can think of is in one of Sir John Harvey Jones’ books. This happened before he got the top job at ICI. He, with colleagues at ICI, decided that they needed to create a committee of the Managing Directors running the subsidiary companies within the group. These were people who reported directly to the board, but weren’t board members. But in reality, they ran the whole business. So imagine what you would think if you were a board member and suddenly you found that all the most important people in the company were meeting as a group to discuss what they were going to do. What could the board do? Ban them from meeting? Turn up at the meeting themselves? In reality, they didn’t have the power to stop it if there was a collective will that this was going to happen. So it happened and, although this was catered for by some subtle administrative support arrangements, there was a shift in power and influence as a direct result — to the benefit of the operational performance of the whole organisation.

When I first worked at Unilever, I was employed in the paper and board division, making what people would call “cardboard” for packaging, sold within the whole group and to external customers. My boss, Glyn, was the Mill Manager. He basically ran the whole operational side of the business while not actually being the most senior person. How did he do this? He created, chaired and ran the daily meeting that discussed and decided what was going to be done operationally. The meeting was an extremely effective way of getting everyone in the same room at least once a day to direct and coordinate activities. The meeting worked with one mind, so no one was going to interfere with what was decided. Too many important people had already put their collective thoughts to any issues and problems and, once the meeting had decided, that is what got implemented. There were limits, of course, but that meeting also controlled the budget submission, and even the capital budget submission as well. The meeting enabled the business to perform and the organisation ran so much better because it was done that way.

So I was schooled early on in Gorilla Management by someone who I now believe was a master of it. It wasn’t much later that I decided I needed to do some myself (although I didn’t realise fully what I was doing at the time). My project was to design and deliver a new integrated production planning and control system throughout the mill, but the project was being delivered by the IT function. There was a team who sat outside my office and after their IT project manager left a contractor was brought in to help fill the gap with guidance from the group’s IT manager. This wasn’t working. The team were rudderless, lacking a sense of urgency and purpose. So one afternoon I grabbed a colleague, David, who I knew well from the IT team and told him we were going to have a project review meeting. He didn’t complain, so I stopped everyone working and got them all into the meeting room to update me and the rest of their colleagues on where they were. For the first time everyone had a view of the project, understood how what they were doing fitted in, and then they committed to what they were going to deliver next.

The contractor who was supposed to be running the project made a snide remark as the meeting broke up, which I ignored, and my colleague David just said “keep going”. The Group IT manager told me not to do it again and “if I wanted to know how the project was progressing you should ask me”. I just said back flatly that “if I thought you knew, I would have asked you”. And I then ran the meeting every week for the next two and a half years. It wasn’t official, but eventually the Director asked where the project had got to and the Group IT manager just pointed him in my direction.

So, Gorilla Management can be done. It is done by getting those directly responsible and involved in running the business or delivering a project to come together to collectively make decisions which they are comfortable with and to then act on those decisions.

The power comes from the group themselves and you can do it if there is a vacuum. most people can see the vacuum and are willing to get involved in fixing the problem.

You can’t do it simply to promote your own position — although that may be the outcome, as it was for Harvey Jones, Glyn and myself. It has to be done for the wider good because something is missing from the way the organisation is run. If you do it for yourself, it will be seen as a cynical ploy and the change won’t last, whereas all the examples above lasted for many years.

And you can probably get fired for doing it too. However, if the need is there and the support from your colleagues is too, because it is a genuine need, then it makes it very difficult to fire you. But it is a risk. Having a very senior protector helps too. Harvey Jones and Glyn didn’t have one; in hindsight I had Glyn, although that was never put to the test.

Good luck.

Mike Bourne

Categories & Tags:

Leave a comment on this post:

You might also like…

Keren Tuv: My Cranfield experience studying Renewable Energy

Hello, my name is Keren, I am from London, UK, and I am studying Renewable Energy MSc. My journey to discovering Cranfield University began when I first decided to return to academia to pursue ...

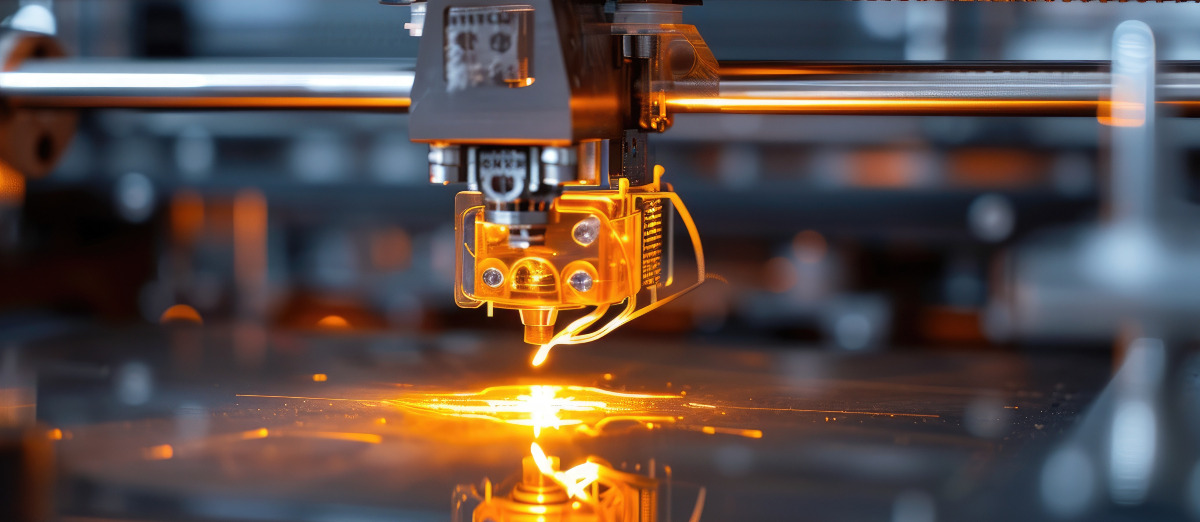

3D Metal Manufacturing in space: A look into the future

David Rico Sierra, Research Fellow in Additive Manufacturing, was recently involved in an exciting project to manufacture parts using 3D printers in space. Here he reflects on his time working with Airbus in Toulouse… ...

A Legacy of Courage: From India to Britain, Three Generations Find Their Home

My story begins with my grandfather, who plucked up the courage to travel aboard at the age of 22 and start a new life in the UK. I don’t think he would have thought that ...

Cranfield to JLR: mastering mechatronics for a dream career

My name is Jerin Tom, and in 2023 I graduated from Cranfield with an MSc in Automotive Mechatronics. Originally from India, I've always been fascinated by the world of automobiles. Why Cranfield and the ...

Bringing the vision of advanced air mobility closer to reality

Experts at Cranfield University led by Professor Antonios Tsourdos, Head of the Autonomous and Cyber-Physical Systems Centre, are part of the Air Mobility Ecosystem Consortium (AMEC), which aims to demonstrate the commercial and operational ...

Using grey literature in your research: A short guide

As you research and write your thesis, you might come across, or be looking for, ‘grey literature’. This is quite simply material that is either unpublished, or published but not in a commercial form. Types ...