Mahdi’s Mustang Project

28/01/2019

Mahdi is a recent Motorsport Engineering graduate at Cranfield University, who is now working as a Research Assistant here at the university.

Find out about the Ford Mustang project that he recently worked on, and why he thinks Cranfield’s brand new course ‘Connected and Autonomous Vehicle Engineering (Automotive)‘, is a must for engineers who are interested in an rapidly-advancing career in autonomous vehicles – covering advanced computing, robotics and network-enabled technologies.

Before coming to Cranfield, I did a Mechanical Engineering undergrad degree at the University of Tehran, and was part of a solar vehicle team and made a solar car for a race in Australia.

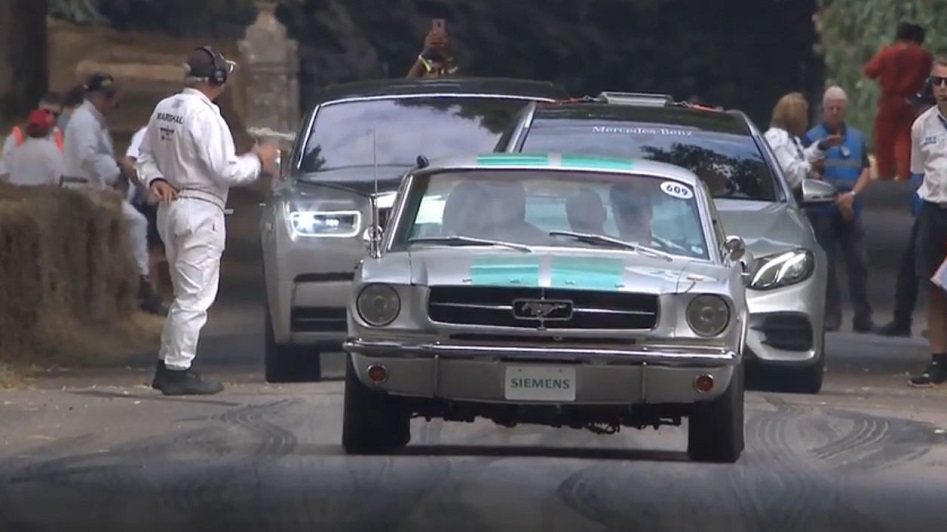

Halfway through my course at Cranfield, when my modules had finished, I began working on a Ford Mustang project with Dr Kim Blackburn and Dr James Brighton, which was pretty cool.

I remember the first Formula 1 race that I watched, which was won by Mercedes’ Nico Rosberg, so the project was a pretty special one for me. That was during Australia 2016 – I watched that race and was just amazed – what those cars were doing. From that moment I was a fan. It wasn’t overnight, but the appeal of motorsport grew during each race I watched. I thought it was cool that it was something that Mechanical Engineers can do – any Engineers can do – so decided that this was what I wanted to do as a job.

Before that all happened, I worked as a mechanic for two years, so I was already into cars. But I didn’t realise that I could go this far. When I realised that such a thing existed, I wanted to do that; it’s all about knowing what university courses are available. The Motorsport programme at Cranfield is one of the most famous in the world, and the connections they have are second to none.

When I came to Cranfield, it was the first time I’d ever visited the UK, but I connected with a Cranfield alumni on LinkedIn who had studied here already when I was working on race cars back home, and he recommended the course to me. I hadn’t ever lived outside Iran before, but had spent one month in Australia. That was my whole experience outside the country, so coming to Cranfield was a big change! I got here on 25 September and started my course two days later. The Masters course was one year, so I only got the chance to go back home for a week during that period.

I was looking for a project to do here so asked Kim if he had anything for me to work on. He said that there was something coming up with Siemens, the Mustang project, which he could let me work on. And that was that! A month later, the car was here and they did all of the mechanical work on it and modified it. What was left was to design a control algorithm to drive the car based on the limited amount of information that we had – which was my job.

Big companies use vision, LIDAR’s – they know where they are and where they’re going. We were doing tests based on GPS and IMU, which is not a lot of information. Especially in Goodwood, because it’s in a rural location with lots of trees, which isn’t great with the GPS. That was the biggest problem we had to tackle.

Looking back, the tests could have been better. There was another autonomous car at Goodwood – the first ever year that had happened – owned by Roborace. They had been doing track tests for months, but what they were doing was slightly different – plus our whole project took little more than six weeks. But that’s the thing; as an engineer you’re always on a short deadline because time is money. The more time you spend on a project, the more you’re spending and vice versa.

The problem that we has was the GPS, because when you don’t have strong GPS the car doesn’t know where it is. And if it doesn’t know where it is, it isn’t easy to know where you’ve got to go. If we had better instrumentation for detection – and more time – we would have been able to develop better algorithms for control. The one good thing is the car doesn’t move too fast, so it has time to lock onto the location.

The GPS we used for the Mustang was roughly the size of a typical smart phone, but autonomous vehicle developers are starting to use LIDAR’s and vision – and not use GPS as regularly.

The GPS we used for the Mustang was roughly the size of a typical smart phone, but autonomous vehicle developers are starting to use LIDAR’s and vision – and not use GPS as regularly.

I’m now a Research Assistant here at Cranfield, and have begun to work on another interesting project. There are different levels of autonomy in a car: manual driving, driver assist, and where the driver can take their hands off the wheel and do other things. But at some point they’ll need to input into some aspect of the vehicle – i.e. it doesn’t completely make its own decision.

What we’re working on now is that transition period, where the car is driving autonomously, and how long it would take for the driver to take over and recognise what’s going on outside the car. And essentially controlling that transition period and making the car stable.

An interesting example of this is the Tesla accident that happened, where they are carrying out tests on level two, ‘driver assist’, not automated driving. This means the driver can take their hands off the wheel and no have to drive the car, but still pay attention to the road and what’s going on around them. The car signalled the driver way before running into a problem, but for some reason the driver didn’t react. It knew something was going to happen, but it didn’t have enough information to drive itself, or something with the algorithm has gone wrong. In this instance the car can’t be blamed.

What we’re doing is working on a higher level of autonomy than that. For example, where you can be on your phone and the car has to cue you in so that you can look up, see what’s going on and take control of the car yourself. Obviously, this depends on your surroundings – if you’re in a busy area you will need to act a lot quicker – that period can take 1.5 – 2 seconds.

Autonomous vehicles are interesting because they will only be able to be introduced to public roads once everyone is using them. But once this is the case, running them will be pretty straightforward as they would all be connected. If you had both autonomous cars and manually-driven cars on the road, that’s going to be complicated. Humans are unpredictable; you can have someone driving over the speed limit, doing unpredictable movements – which could cause an accident. Due to this, it’s hard to put a timescale on when this will happen – maybe in 50 years we’ll have only driverless cars.

Driverless cars could happen now – the technology is already there – but alongside getting the buy-in of everyone that they would have a positive impact, there are other details that need to be considered:

Insurance: how will that work, and will there be only one insurer?

Ownership of a vehicle: do you want to own an autonomous car, or do you want to just get into one and go where you want to go?

Emissions would go down, accidents would be reduced, and you could have a whole network of cars controlled by one algorithm that knows where your car wants to go.

If you’re an engineer or a university engineer graduate and are looking to study in the field of Autonomous Vehicles, Cranfield is launching a new course this year, ‘Connected and Autonomous Vehicle Engineering (Automotive)’ CAVE (A), which specialises in the area. You’ll need a lot of practical experience, so just reading the control structure and algorithms from a book is a good thing – but it isn’t everything. And that’s the opportunity that CAVE (A) students will have – the opportunity to work on a car – and have it go wrong a couple of times. That’s where Cranfield is different. You get all this hands-on experience and opportunities which makes the course unique. There’s also a lot of industry connections, which turns a student project into a real-life project. As an engineer you have a perspective of everything that’s going on, which is a great thing.

We also have a test track here, which is something you don’t see at other places. Students get the opportunity to do a lot of testing, and this was something that was particularly helpful during the Mustang project – we just went there and tested every day for two weeks.

If the Connected and Autonomous Vehicle Engineering (Automotive) sounds like the master’s degree for you, make sure you apply now before spaces fill up!

Categories & Tags:

Leave a comment on this post:

You might also like…

Setting up a shared group folder in a reference manager

Many of our students are now busy working on their group projects. One easy way to share references amongst a group is to set up group folders in a reference manager like Mendeley or Zotero. ...

Company codes – CUSIP, SEDOL, ISIN…. What do they mean and how can you use them in our Library resources?

As you use our many finance resources, you will probably notice unique company identifiers which may be codes or symbols. It is worth spending some time getting to know what these are and which resources ...

Supporting careers in defence through specialist education

As a materials engineer by background, I have always been drawn to fields where technical expertise directly shapes real‑world outcomes. Few sectors exemplify this better than defence. Engineering careers in defence sit at the ...

What being a woman in STEM means to me

STEM is both a way of thinking and a practical toolkit. It sharpens reasoning and equips us to turn ideas into solutions with measurable impact. For me, STEM has never been only about acquiring ...

A woman’s experience in environmental science within defence

When I stepped into the gates of the Defence Academy it was the 30th September 2019. I did not know at the time that this would be the beginning of a long journey as ...

Working on your group project? We can help!

When undertaking a group project, typically you'll need to investigate a topic, decide on a methodology for your investigation, gather and collate information and data, share your findings with each other, and then formally report ...