Military Tactics and Command & Control – Fact or Myth?

10/11/2017

A few weeks ago we looked at the way the military works and concluded that they do not practice what is commonly regarded as “Command & Control” – but instead use something referred to as “Mission Command”.

Before we look at this approach, let me make some observations from some of our travels: Just what exactly do people mean by Command & Control? It was defined in our previous blog as “I tell you what to do and then check to see if you have done it”. Our general view is that people come to work with a brain and want to use it to do a good job and to add value, and don’t appreciate being told what to do.

And we have found that Command & Control is bit like the European Union – last year’s referendum campaign seemed to be “Everything’s wrong and it’s all because of Brussels!”. Command & Control seems the euphemism for all that is wrong with today’s western management style.

However, we have seen in both large private and public sector organisations teams where the front-line appears to prefer being told what to do rather than deciding for themselves (let’s assume for now using evidence-based decision-making). The reason given, it seems, is that if there is a problem arising from what they have done, they can blame whoever told them what to do, rather than taking the responsibility for themselves. Others say, “Just tell me what to do, that way I don’t have to think and can go home with my pay-packet and get on with my life”. In other situations, there is the impossible situation where teams are “Held Accountable for…”, but have no “Responsibility for …” and I believe it is this particular problem that leads to massive frustration and dissatisfaction. I personally saw this in action in a large Police Force in the North of England in the early 2000’s (using now disproven techniques adopted from the US) – generating untold stress and absence and sickness across the organisation. You may have an opinion on this…..

But, is all this really Command & Control? I would argue that it is not. It’s just poor management practices. If you think about it, Command & Control can only work where you have the opposite of Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity and Ambiguity (VUCA). If a (world)-system is highly volatile (e.g. in any service that is affected by the weather, for example road-side repair/rescue, when one day it’s beautiful, dry and sunny and little going on, the next day blizzards and drivers unused to the snow) you have severe challenges knowing how many staff and vehicles (of the right sort) are required at any one time. If that system is uncertain (e.g. where the last time you provided a response in a certain situation it worked, but this time, that exact same response does not work), tried and tested (and in particular, so-called “Best Practice”) does not always work. If that system is complex, it is impossible for a small executive team at the centre (or top – how do you draw it?) of an organisation to have all the knowledge and experience to conduct work at the front-line. If it’s ambiguous, where several responses to an issue could work, there’s no manual telling you which one will work. The only way to handle this kind of system is to build in a feedback mechanism responding at the appropriate time-scales for that system or be so-called “Agile”.

So Mission Command is designed to handle situations military units encounter in theatre where conditions can often be described as VUCA. Under such conditions, rational, analytical, and directed approaches (such as the traditional interpretation of Command & Control) are ineffective as these are based on the assumption of stability and predictability. Hence the need for an approach that offers flexibility and agility yet guides individuals towards the same, shared objective (Mission Command).

And VUCA precisely describes the world most of our organisations inhabit – so Mission Command is a useful model – meaning make sure you’ve got good leaders to develop and share a common Purpose, and ensure you keep all your good people out to the front-line who will operate almost autonomously (understanding and aligned to Purpose (or Sub-purpose), within a small number of clearly defined business rules and constraints).

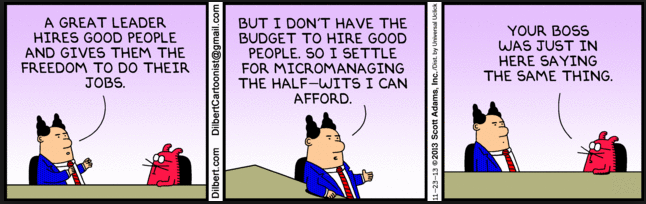

Or you could take the Dilbert approach …

More in the next blog….

Categories & Tags:

Leave a comment on this post:

You might also like…

Company codes – CUSIP, SEDOL, ISIN…. What do they mean and how can you use them in our Library resources?

As you use our many finance resources, you will probably notice unique company identifiers which may be codes or symbols. It is worth spending some time getting to know what these are and which resources ...

Supporting careers in defence through specialist education

As a materials engineer by background, I have always been drawn to fields where technical expertise directly shapes real‑world outcomes. Few sectors exemplify this better than defence. Engineering careers in defence sit at the ...

What being a woman in STEM means to me

STEM is both a way of thinking and a practical toolkit. It sharpens reasoning and equips us to turn ideas into solutions with measurable impact. For me, STEM has never been only about acquiring ...

A woman’s experience in environmental science within defence

When I stepped into the gates of the Defence Academy it was the 30th September 2019. I did not know at the time that this would be the beginning of a long journey as ...

Working on your group project? We can help!

When undertaking a group project, typically you'll need to investigate a topic, decide on a methodology for your investigation, gather and collate information and data, share your findings with each other, and then formally report ...

From passion to purpose: My journey at the Pinnacle of Aviation

By: Sultana Yassin Abdi MSc Air Transport Management, Current Student Born and raised in the vibrant landscape of the UAE, with roots stretching back to Somalia, my life has always been ...