Flooding in the Aire: why we can reduce floods in the UK

19/01/2016

As a researcher looking at sediment transport and storage in the Leeds Flood Alleviation Scheme, I need rain. Rain causes surface runoff and runoff causes erosion, which eventually results in sediment transported towards and within the river. When I began my work, everyone told me that the rain would be the least of my problems: “It’s always raining in Leeds”, they said. However, this hasn’t been the case in Leeds during the past year. It was hard to imagine how vulnerable Leeds actually is to flooding.

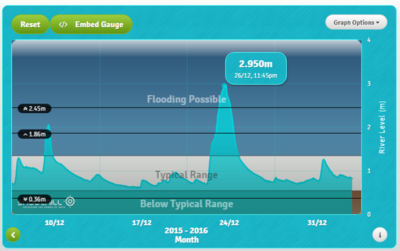

Then, November brought several storm events causing the river levels to rise close to flooding. Gradually the soil became more and more saturated over the course of the wet month of December until storm Eva hit Yorkshire at Christmas. On the morning of the 26th of December this eventually caused the River Aire in Leeds to quickly rise to its highest level ever recorded (almost 3m at Crown Point), and resulted in the flooding of major parts of the city. (The highest level before that was 2.5m in 2007, when the city narrowly escaped flooding).

Flooding happens in many parts of the world. My home street in Belgium has flooded several times. I’ve seen the impact of flooding along the Jamuna River in Bangladesh, and now the Aire has flooded in Leeds. But there is a big difference in how we perceive these flood risks. In Bangladesh, for many people floods are a fact of life. They know that living along the banks of the Jamuna means that one day you will likely have to move because of flooding. It’s just too big to stop. Here on the contrary, our rivers are not that big, so we get the idea that we are able to stop it. If that doesn’t happen, we get angry with the river that has ’caused’ this and angry with the government and their agencies for not preventing the disaster.

But can we actually stop such a huge amount of water? Well, partially we can. Or at least, we can manage it better than we do now. We are part of the problem. By building houses around our rivers, consolidating their banks and separating them from the floodplains, we’ve taken the space the river needs to flow. With increasing urbanisation and agriculture, we have sealed soils and thereby prevented infiltration of water in the soil. There is more surface water and less space for it to flow, resulting in a higher flood risk. So if we have partially caused the problem, we can do something about it. We can not only build flood walls, but we can also (re)create more space for the water to flow, slow down the water and increase infiltration to reduce surface flow.

That’s where flood risk management and flood alleviation strategies come in. In Leeds, construction started last year on a Flood Alleviation Scheme (FAS) that will reduce flood risk within the heart of the city. It includes the installation of movable weirs and other measure which improve flood conveyance. These measures are designed to reduce the levels of flood flows (i.e. creating more space for the water), thereby reducing the need for high flood walls. But unfortunately these measures are still under construction and the storm came too early…

So what is the link between sediment and flood alleviation? Well, in many cases, hard engineering is not the entire solution. Whilst the current scheme in Leeds is the best management compromise, the solution increases the likelihood of sediment which will have ecological impacts and maintenance implications (such as the need for dredging). My project is developing new evidence on sediment transport and storage in Leeds to inform future maintenance operations which can ensure long-term flood protection. It is also developing a quick, reliable ‘sediment fingerprinting’ method to identify where sediment is coming from upland. This knowledge will help us to move towards catchment-based flood risk management by creating opportunities to tackle soil erosion in a targeted way and reduce the amount of sediment coming into the river.

My wish for Leeds in the coming year is just enough rain to get some good sediment samples, but not that much to cause actual flooding!

Find out more about fluvial geomorphology research at Cranfield University.

Categories & Tags:

Leave a comment on this post:

You might also like…

Commuting, collaborating and growing: My first term experience at Cranfield

My first term at Cranfield University has been an extremely positive and rewarding experience. While the course has been intense at times, it has pushed me in the best possible way and allowed me ...

Sourcing country analysis – a guide to Library sources

For those researching a country, you will find that country information tends to take two forms: Analysis - country reports are descriptive reports covering most areas of interest on a country. They contain an analysis ...

The degree that launched my marketing career

Insights from Tayo George, Strategic Marketing MSc Alumni I chose the Strategic Marketing MSc at Cranfield because I wanted a programme that combined academic rigour with practical, commercial relevance. The emphasis on applied learning, ...

From national service to Environmental Engineering: My journey to Cranfield

Postgraduate study is often a defining step in shaping one’s academic and professional direction. For me, pursuing an MSc in Environmental Engineering at Cranfield University has been both a personal and professional adventure—one that ...

From limited experience to a UK marketing career

Top tips for postgraduate marketing students by Elnaz Dashchi, Strategic Marketing MSc alumni Coming into the postgraduate Strategic Marketing MSc, I did not have a lot of professional experience - and that made me ...

My journey to Cranfield as an FIA Motorsport Engineering Scholar

"You don’t need to fit a stereotype to succeed in engineering or motorsport. You need curiosity. Resilience. And the confidence to take up space." In this blog, Sanya Jain, current MSc student and FIA ...