An overview of Tourette’s Syndrome

06/06/2022

If I write the word ‘Tourettes’, the first thing you will likely think about is swearing. That’s not unusual because in the popular media it’s normally the first thing that’s mentioned when someone comments on the condition. But, coprolalia (from the Greek ‘kopros’ meaning dung, and lalia meaning speech) affects only 15% of those with Tourette’s Syndrome (TS).

June 7 is Tourette Syndrome Awareness Day so it feels appropriate to share some knowledge about it. TS is a childhood-onset neurological disorder characterized by involuntary physical movements known as motor tics; and at least one phonic tic (noises and words). Many of those with TS will also have a co-condition such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), and Anxiety.

TS typically manifests before puberty and is more common in boys than girls. In population-based and clinical sample studies tic severity typically peaks between 8 and 12 years of age. For many the onset of adulthood coincides with a noticeable reduction in severity. However, many individuals who have TS in childhood continue to have tics into adulthood.

The condition is named after Dr Georges Gilles de la Tourette (1857-1904) who first identified the medical phenomenon in 1884. He described the condition that he observed in nine patients who were exhibiting involuntary tics. At that time the condition was thought to be psychiatric but the work of Arthur and Elaine Shapiro in the 1970s challenged this and, through extensive work, promoted the view of it being neurological in origin.

The neurobiological causes of tics are, like much in the field of neurodiversity, under regular review and research. However, studies and brain imaging indicate the involvement of the brain circuit that controls movement execution, habit formation and reward (the ‘cortical– striatal–thalamocortical’ (CSTC) pathways. Other research has indicated that it may have an inherited component – with parents and children sharing TS-type behaviour.

There is a paucity of studies into adults with TS, especially those in work and this is an element of continued research by Cranfield University into neurodiversity. However, what is known is that many adults with TS do feel that it interferes with their life. Robertson et al. (1993) notes that, in comparison to the general population, adults with TS have higher social anxiety, depression, and obsessionality. The TS population also has higher levels of unemployment and problems in dating and in making and keeping friends, in addition to facing social and occupational discrimination.

TS can also have several physical consequences such as musculoskeletal or neuropathic pain, tissue damage resulting from tic repetition (e.g., stress fractures), or injury caused by striking an object when performing a tic (Fusco, et al. 2006). Sometimes tics can manifest in severe, continuous, non-suppressible, physically, and mentally demanding events called ‘tic attacks’ (also called ‘tic fits’) that can leave people exhausted.

It is initially strange to be with someone who is making noises or ticking. But that is because many of us may not have come across it in our working lives. That in itself is a powerful point. We should. The societal model of neurodiversity is one that pronounces that it is society that places barriers in the way of people with a difference.

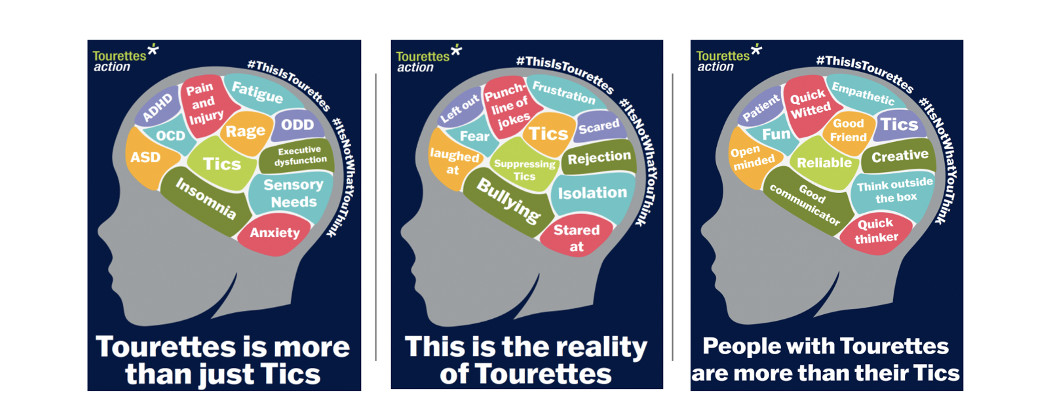

Those with TS, like all neurodivergents, have so much to give to society and to companies that employ them. The charity Tourette’s Action has produced a series of powerful posters that frame this so well. The reality of Tourette’s is the tics and comorbidity, it is the way society regards people as being the punchline in jokes or being left out – but, it is also the innovative, quick thinking, empathetic, reliable element of the person that is just as important.

As our research into neurodiversity continues it is worth continuing to emphasise that the need for understanding and education is paramount.

Tourette’s Action can be contacted via:

https://www.tourettes-action.org.uk/

You can also take a look at this video from Tourettes Action that looks to dispel the myths around TS.

References:

Champion, L. M., Fulton, W. A., & Shady, G. A. (1988). Tourette syndrome and social functioning in a Canadian population. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 12, 255–257.

Fusco, C., Bertani, G., Caricati, G., & Della Giustina, E. (2006). Stress fracture of the peroneal bone secondary to a complex tic. Brain and Development, 28, 52–54.

Leckman, J.F. (2002). Tourette’s syndrome. Lancet. 360: 1577–1586.

Leckman, J.F. (2012). Tic disorders. British Medical Journal, 344: d7659

Robertson, M. M., Channon, S., Baker, J., & Flynn, D. (1993). The psychopathology of Gilles de la Tourette’s syndrome: A controlled study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 114–117.

Categories & Tags:

Leave a comment on this post:

You might also like…

Keren Tuv: My Cranfield experience studying Renewable Energy

Hello, my name is Keren, I am from London, UK, and I am studying Renewable Energy MSc. My journey to discovering Cranfield University began when I first decided to return to academia to pursue ...

3D Metal Manufacturing in space: A look into the future

David Rico Sierra, Research Fellow in Additive Manufacturing, was recently involved in an exciting project to manufacture parts using 3D printers in space. Here he reflects on his time working with Airbus in Toulouse… ...

A Legacy of Courage: From India to Britain, Three Generations Find Their Home

My story begins with my grandfather, who plucked up the courage to travel aboard at the age of 22 and start a new life in the UK. I don’t think he would have thought that ...

Cranfield to JLR: mastering mechatronics for a dream career

My name is Jerin Tom, and in 2023 I graduated from Cranfield with an MSc in Automotive Mechatronics. Originally from India, I've always been fascinated by the world of automobiles. Why Cranfield and the ...

Bringing the vision of advanced air mobility closer to reality

Experts at Cranfield University led by Professor Antonios Tsourdos, Head of the Autonomous and Cyber-Physical Systems Centre, are part of the Air Mobility Ecosystem Consortium (AMEC), which aims to demonstrate the commercial and operational ...

Using grey literature in your research: A short guide

As you research and write your thesis, you might come across, or be looking for, ‘grey literature’. This is quite simply material that is either unpublished, or published but not in a commercial form. Types ...