The Use of Best Practice – the Well-trodden Path to Mediocrity?

12/06/2017

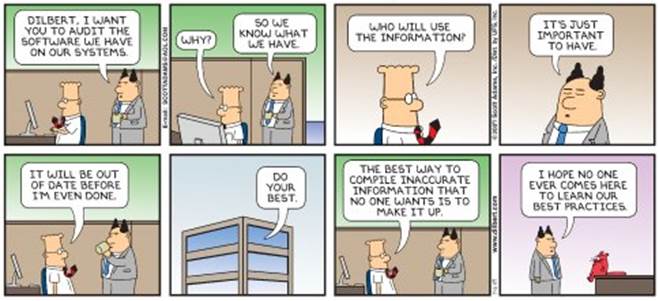

This is likely to be controversial, so I look forward to any (evidence-based) comments readers may have that counter my colleagues’ and customers’ observations on the use of Best Practice (or Best Value, or Best anything else for that matter). The root-problem behind the use of so-called Best Practice is founded in one of our previous blogs last December “Paying Attention to Detail” where we introduced the concept of “Simplistic on the Near-side of Complexity” vs “Simplicity on the Far-side of Complexity”. Best Practice is too often a synonym for “Copying” – i.e. the Simplistic on the Near-side, giving rise to “improvement” projects doomed to success (“It worked over there, why not here?”). It seems to be more prevalent in the Public Sector compared with the Private Sector. On the other hand, the usual human resistance to change “It won’t work here – it’s different!” also is rooted in the same problem – just used in an adversarial way to resist change.

So we’ll tackle 3 questions:

- Why does the use of Best Practice so often deliver negative results?

- Do we have examples where the use of Best Practice delivers negative or less than expected results?

- Where have we seen use of Best Practice work well?

Why: Digging a little deeper, when either Public Sector or Private Sector businesses (and I use the word business for a reason – subject of another blog perhaps?) implement a successful improvement project (be it a small change project or a massive transformation programme), one of the key reasons for success is that the project team takes significant care to really understand three aspects – The System (World-system, not IT System) they were working in, the Context (primarily driven by Purpose, but includes Environment (e.g. geography, geo-demographics, time of day/week/year, socio-economic factors)) they were working in and the AS-IS and TO-BE states. It’s complex right? Because an improvement worked in one place, lifting and shifting it or rolling it out across an entire organisation could prove disastrous. You have to understand the complexity first.

Examples: I’m sure readers will have a sack-full of examples. I’ll quote just two, one from Police and another from Global Supply-chain.

Some while ago, a Commander in a large Metropolitan Force had clear evidence that opportunistic theft, committed by itinerant/marauding criminals, was dominating their crime figures in his area. He put in place a number of (and I don’t know the politically correct term – so here goes) “trap” operations and successfully dramatically brought down crime in his area. Other Commanders and the Senior Command Team noticed this, and declared it “Best Practice” and it was rolled out across the Force. Result – dismal failure. Edict: Stop all trap operations in ALL areas (including the original successful area)!

In a massive global pharma company, the global “Best Practice” approach to Forecast Accuracy (essentially evaluating if you sell as much as you forecast in any given period (i.e. month in this case)) is to aim to get Forecast Accuracy in the high 80% – 90% area. As high as possible. The evidence, as we revealed through careful analysis of their formula for Forecast Accuracy, was that it was mathematically impossible to achieve anything above the mid 80% level no matter how good they were. Why? Because Forecast Accuracy was defined, not as the simple difference between Forecast Sales and Actual Sales (as you might think), but as a complex formula comprising ratios and differences of 11 different variables! In one case, the low levels of Forecast Accuracy achievement (setting off a witch-hunt involving 20 analysts and managers) was due, not to the difference between Forecast and Actuals, but to one of these other variables in the formula – the number of Stock Items taken into the calculation! And this is a Global Best Practice Indicator!

Where: Where has best Practice worked well? Wherever true learning has taken place, understanding the issues in the “Why” point above. This learning (not necessarily the doing) can then be built into Education and Training material for people at the front-line as a “Playbook” – and this is the basis of the OODA Loop (Observation, Orientation, Decision, Action – type it into Wiki and get all the details). So whenever you are told use “Best Practice”, or use “What Works”, it may be just worth pressing the “Pause” button and asking Why?

Otherwise, you will be just beating the well-trodden path to “Regression of the Mean” – or in other words – Mediocrity!

Categories & Tags:

Leave a comment on this post:

You might also like…

Commonwealth Scholarships play a critical role in developing sustainability and leadership in Africa

Q&A with Evah Mosetlhane, Sustainability MSc, Commonwealth Distance Learning Scholar What inspired you to pursue the Sustainability MSc at Cranfield? I was inspired to pursue the Sustainability MSc at Cranfield because of the university’s ...

How do I reference a thesis… in the NLM style?

You may be including theses within your research. When you do so you need to treat them in the same way as content taken from any other source, by providing both a citation and a ...

Introducing… Bloomberg Trade Flows

Are you interested in world trade flows? Would it be useful to know which nations are your country's major trading partners? If so, the Bloomberg terminal has a rather nifty function where you can view ...

Cranfield alumni voyage to the International Space Station

Seeing our alumni reach the International Space Station (ISS) has a ripple effect that extends far beyond the space sector. For school students questioning whether science is “for them”, for undergraduates weighing their next ...

From classroom to cockpit: What’s next after Cranfield

The Air Transport Management MSc isn’t just about learning theory — it’s about preparing for a career in the aviation industry. Adit shares his dream job, insights from classmates, and advice for prospective students. ...

Setting up a shared group folder in a reference manager

Many of our students are now busy working on their group projects. One easy way to share references amongst a group is to set up group folders in a reference manager like Mendeley or Zotero. ...