Coordination, Can we do it Smarter?

26/10/2015

Coordination is a word that we use frequently and think we understand. However, if my recent experience holds true, it is also a word that few are able to define clearly. If we are to be SMART about the way we manage our effort to coordinate, we need to be clear about what constitutes this construct.

By Dr Mike Lauder (Guest Author)

Coordination is a word that we all know well, use frequently and think we understand. Many clients claim it is a central part of their role within their organisation, that it is a central part of their duties. However, if my recent experience holds true, it is also a word that few are able to define clearly.

Why is this important? Within my line of research, which concerns organisational failure as a performance management issue, I often read that such and such a failure was due to a lack of coordination. If however we are unable to agree on what this construct means, how can we know what good coordination should look like? How can we ensure such failures do not occur? In order to address this problem as part of my current research, I needed to be clear what constitutes coordination. My work is looking at how we might cope when chaos is the natural, or normal, state. In this context I see the need to recognise that our span of control is far more limited than we often portray it as being. This means that, far from controlling events, we find that we are only able to influence the actions of the other parties involved. In this context influencing, resilience, agility and coordination become our main tools. For those like me seeking to find ways of preventing organisational failure, an understanding of coordination then becomes a key issue. Therefore, in order to make progress, I needed to define the ideas that are encompassed by the word coordination.

The purpose of this note is to provide those who contributed to this quest with feedback on my thinking at this point.

For those who have not been involved in this conversation to date, I will provide a short summary. As I said above, my interest is preventing organisational failures, or to be more specific, the prevention of “failures of foresight”. In my second book I looked at a process appropriate to this task based on Barry Turner’s Disaster Incubation Theory. What became clear during this work was that the world in which we operate is far more chaotic than we like to think; our span of control is far less than we would like to think. In this context, which I refer to as normal chaos, resilience and agility are more important than plans and standards; coordination and influence is all that is actually available to us rather than the command and control that we would like to have. As a result of this thought process I sought to develop a gold standard for coordination that I could test against a historical case study. The case study I chose was the American landings on OMAHA beach on the 6 June 1944. My aim was to look at this very interactive complex process to see how they coordinated the various activities involved and to identify where they succeeded and where they did not in a bid to determine why each result occurred. The story that is developing so far is not the one more commonly told! However, before I can develop this storyline further, I have first to develop my ideas on the subject of coordination.

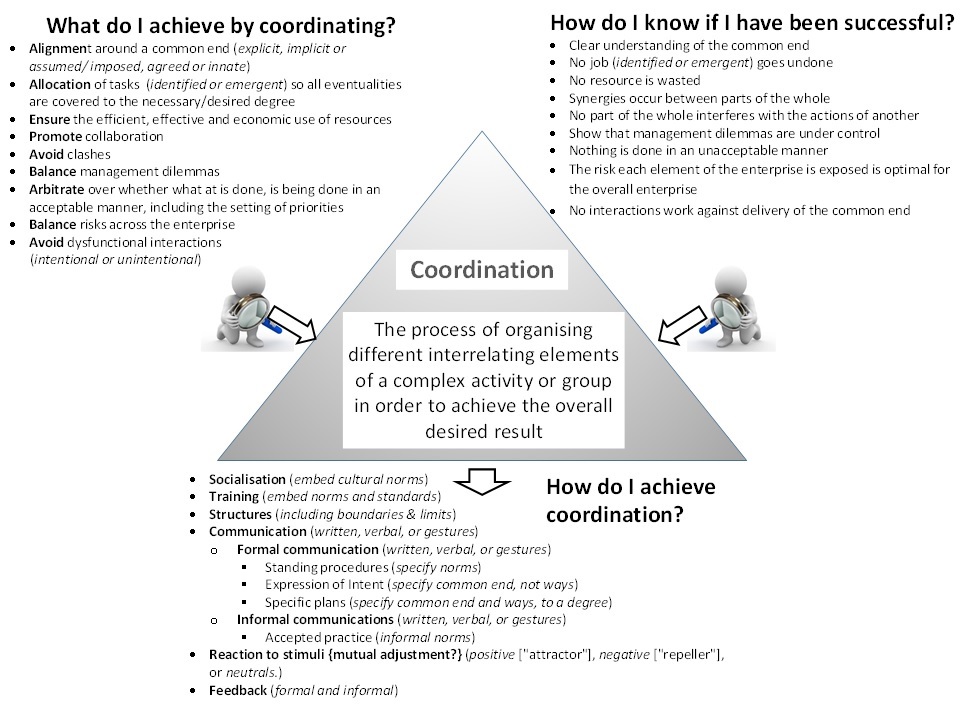

My quest started with a dictionary. In the end I synthesised the definitions from four general dictionaries in order to delineate my starting point. To test the definition I decided to use the framework provided by what is known as the “10 minute MBA”. This asks four questions: these are, where are we now (this is our current confused state), where do we want to be (know our goals for coordinating), how will we get there (how we will coordinate), and when will we know we have arrived (performance measure for coordination)? In short, I would try to clarify the purpose of coordination, the means (methods) we use to coordinate and what successful coordination would look like. I had determined that answers to these questions would enable me to see how consistent my definition was (or as it has turned out, my definitions were) with the practice of coordination. Figure 1 represents a schema of my method.

As part of my quest I sought help from a dozen colleagues at Cranfield (both DBAs and faculty). I asked them, what I hoped was, an unprescriptive question; I received a wide variety of answers. I was pointed to the work of Fayol on POCCC, which lead to Gulick’s work on POSDCORB and the subsequent derivative work that defined coordination from their academic perspective (hence “definitions”). I was also pointed to ideas that coordination was about, amongst other things, aligning, balancing, arbitrating over what is acceptable and utilising constructive tension. In addition they made me think about whether that which is inherent within coordination is explicit or assumed. What was also clear from the replies was the tendency to conflate definition, goals and means as if they were one and the same. I have therefore attempted to draw a line between each.

From all these inputs I now have a suggestion of what we might mean when we use the term coordination. I have two possible definitions. The first synthesised from general dictionaries and the second from academia. These are presented in Table 1. (It should be noted that I have found no academic work that goes further than just defining the term: I have, as yet, found no studies that examine how we achieve the desired end or even define the desired end.)

Table 1 – Defining Coordination

| Source | Definition |

| General Dictionary | The process of organising the different elements of a complex activity or organisation in order to achieve the overall desired result |

| Academic Consideration | The duty of interrelating the various parts of the work: binding together, unifying and harmonising activities and efforts to maintain the balance between the activities of an organisation. |

The clear difference between the two definitions is the notion of coordination as a process or a duty. I favour the idea of it as a process. A final synthesis of these two definitions ends with the word being defined as:

The process of organising* different interrelating elements of a complex activity or group in order to achieve the overall desired result.

* Here we still need to define the goals of organising. These are seen, from these definitions, to include unifying, harmonising, binding together and maintaining balance.

While the academic definition provides a list of goals, this is not considered to be definitive. Discourse exposed some clear ideas about what we are trying to achieve through coordination and how success may be measured if perfection was achieved. These ideas are set out in Table 2. It is important to note that, in practice, goals may not be explicit and may only emerge as events develop.

Table 2 – Coordination: Goals and Success Measures

| What do I achieve by coordinating? | How do I know if I have been successful? |

| · Alignment around a common end (explicit, implicit or assumed/ imposed, agreed or innate) | · Clear understanding of the common end

|

| · Allocation of tasks (identified or emergent) so all eventualities are covered to the necessary/desired degree | · No job (identified or emergent) goes undone

|

| · Ensure the efficient, effective and economic use of resources | · No resource is wasted

|

| · Promote collaboration | · Synergies occur between parts of the whole

|

| · Avoid clashes | · No part of the whole interferes with the actions of another |

| · Balance management dilemmas (all those issues that cannot be resolved: e.g. trading off competing objectives and maintaining stability and order while promoting creativity and innovation or managing constructive tensions.) | · Show that management dilemmas are under control as much as they need to be

|

| · Arbitrate over whether what is done, is being done in an acceptable manner. This would include the setting of priorities

|

· Nothing is done in an unacceptable manner (e.g. whereas insider trading is not normally acceptable, within a criminal enterprise it may be.) |

| · Balance risks

|

· The risk each element of the enterprise is exposed to is done on the basis of what is optimal for the overall enterprise |

| · Avoid Dysfunctional Interactions (intentional or unintentional) | · No interactions work against delivery of the common end |

While most of these goals are self-explanatory, I will take a moment to ask a question of one and explain the last one, “Avoiding Dysfunctional Interactions”. The question I ask is what is coordination without a purpose, a common end? Is it coordination if it does not have a purpose? While some argue it is not, I feel that it is. I would suggest however that what is assumed to be the common end by one party may contradict the views of some of the other parties involved. While we mainly focus on what we are trying to achieve, our common end, we need to be conscious that not everyone connected to the enterprise may support this objective, not everyone may wish to be coordinated. This lack of acceptance may occur in different forms of resistance; it may be passive, active, unintentional or intentional. It may manifest as some unintended consequence of an act initially thought to be beneficial, as reluctance to adopt some change or in a wilful act of sabotage. Successful coordination will need to be aware of this force, identify it and overcome it.

So how might we affect coordination? The means available need to be considered in two dimensions. On the first dimension we would list the tools available and on the second we would rate our ability to exert control using the tool. Depending on the circumstances at the time these tools may offer direct and immediate control of events, may only indirectly influence events or may offer next to no influence at all. The tools by which we may seek to coordinate our activities or group are set out in Table 3.

Table 3 – Coordination Tools

| How do I achieve coordination? |

| · Socialisation (embed cultural norms)

· Training (embed norms and standards) · Structures (including phasing, pacing, boundaries, way markers (time, space or other resources) & limits) · Communication (written, verbal, or gestures) · Formal communication (written, verbal, or gestures) · Standing procedures (specify norms) · Expression of Intent (specify common end, not ways) · Specific plans (specify common end and ways, to a degree) · Informal communications (written, verbal, or gestures) · Accepted practice (informal norms) · Reaction to stimuli {mutual adjustment?} (positive [“attractor”- pulling towards the desired end], negative [“repeller”- pushing away from the desired end], or neutrals [these are decoy phenomena that you have to avoid, they neither attract nor repel but are simply in the way of you achieving your goal.]) · Feedback (formal and informal) |

Figure 2 consolidated all these ideas for those who find such depictions helpful.

Now having articulated the coordination construct, I feel that it is also necessary to differentiate between coordination and control. I see control as being where there is a direct mechanism available by which the output of a system can be manipulated within a crucial timescale. It also has to be recognised that these mechanisms may offer immediate and precise manipulation or they may be somewhat less precise such as offered by a badly worn mechanical linkage. While this might suggest that control is therefore a subset of coordination, I feel that is a debate for another day!

While I know that I still have some way to go in my understanding of coordination as a factor within organisational failure, I feel that some progress has been made thanks to the inputs of my colleagues. I now have some specific factors to look out for and examine within my current case study; this is more than I had before. Should any reader take issue with what I propose or has any other comment, I would welcome their contribution.

—–

Dr Mike Lauder is an alumnus of the Cranfield DBA programme. His first book “It should never happen again” was published by Gower in 2013 and his second book “In Pursuit of Foresight”, also from Gower, is due to be published in November.

Categories & Tags:

Leave a comment on this post:

You might also like…

My Apprenticeship Journey – Broadening Horizons

Laura, Senior Systems Engineer at a leading aircraft manufacturing company, joined Cranfield on the Systems Engineering Master’s Apprenticeship after initially considering taking a year off from her role to complete an MSc. Apprenticeship over MSc? ...

The Library app is back!

The Library app is back! It's exactly the same as before (although it will get a fresh look in a few months) and if you hadn't removed it from an existing device it should just ...

PhD researcher at the IF Oxford Science and Ideas Festival

IF Oxford is a science and ideas Festival packed with inspiring, entertaining and immersive events for people all ages. PhD researcher, Zahra attended the festival. Here she shares what motivated her to get involved. ...

What leadership skills are required to meet the demands of digitalisation?

Digital ecosystems are shifting the dynamics of the world as we know it. With digitalisation being a norm in the software industry, there is currently a rapid rise in its translation ...

My PhD experience within the Centre for Air Transport at Cranfield University

Mengyuan began her PhD in the Centre for Air Transport in October 2022. She recently shared what she is working on and how she has found studying at Cranfield University so ...

In the tyre tracks of the Edwardian geologists

In April 1905 a group of amateur geologists loaded their cumbersome bicycles on to a north-bound train at a London rail station and set off for Bedfordshire on a field excursion. In March 2024 a ...